The three things investors need to know this week

The Fed has pivoted back into hawkish mode. While our cardinal rule has been and shall remain, that we “don’t fight the Fed”, we now know that “forward guidance” is less potent than before

The Fed delaying rate cuts may have a knock-on effect on other central banks and could deteriorate corporate balance sheets across the globe.

The duration trade is now an even riskier one.

Of ancient soothsayers, Pythia, the high priestess of Apollo at Delphi, was considered the more reliable. Why? Because she was clever. She understood forecasting to be a dangerous business. Forecast the future too accurately, people might get angry, or they might pressure you to do it again until you eventually fail. In both cases, they end up hating you. Forecast the future too loosely, and they don’t trust you from the start. Forecast good news that don’t play out or they miss expectations or just forecast bad news, independent of whether they play out or not, people still hate you. Only forecasting good news early and always right will make anyone like you. All other outcomes are bad, The problem was that so many bad outcomes don’t make for a good business model. And Apollo’s priests needed money.

Thus did Pythia chew psychotropic leaves and give very wide predictions, for people to read into them their own desires. The late Daniel Kahneman would call this “confirmation bias”.

Rich merchants were the best clients. A lot of money, no complaints, lest one risk upsetting the vengeful and prickly God. But once in a blue moon, there came a real crisis, and Pythia needed to be extra careful. In 480 BCE, a few weeks after Xerxes defeated Leonidas and his 300 (more like 1500 but why mess with a good movie) in Thermopylae, he marched on Athens. The city was doomed. So officials run to Pythia and asked her what to do:

“Wooden walls will save the city”, she exclaimed.

Half of them understood “Wooden walls” to mean Athens’ powerful navy. The other half took it literally, barricaded themselves on the Acropolis and build wooden walls around it. The first cohort emerged victorious in the famous battle of Salamis, which turned the tide of the Persian Wars and preserved western civilisation. The other ended up ridiculed by Herodotus, not to mention unceremoniously barbecued. Old Pythia smiled. She was right either way.

The point is that forecasting is, for the most part, little more than a brain exercise of little consequence. Wide predictions serve marketing purposes. Accurate predictions, done properly, must always update the forecast with new information. “When the data changes, I change my mind. What do you do?”, John Maynard Keynes famously said. But once a while, a forecast is so important that needs to be right from the start, exposing the limits of this brain exercise.

What is the forecast the world has been waiting for? When will American rates come down. Little is more important, or more difficult, than trying to predict interest rates in an age of unstable inflation.

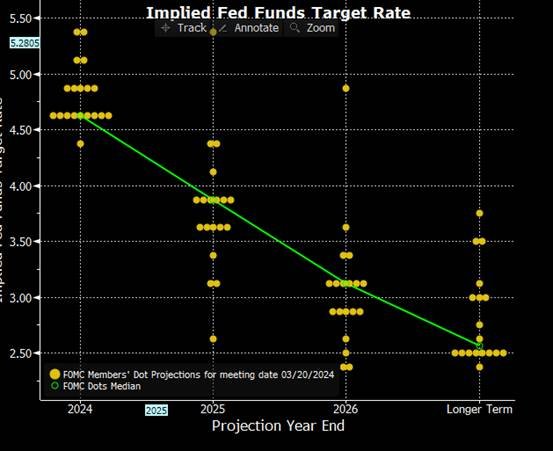

In the past decade and a half, after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the investment world turned to “Fedwatching”. The Federal Open Markets Committee is comprised of roughly 18 individuals, about 12 of whom are voting at any given time. We dissected every word, every preposition, compared with previous statements, and reached our conclusion. The Fed called it “Forward Guidance”. Scarred after the GFC, they wanted to make sure that investors had ample warning before any rate moves. The Fed’s “Dot Plot”, an informal and anonymous survey on where Fed officials see rates.

Forward guidance worked well in an environment of low economic volatility we called “The Great Moderation”. Chinese exported deflation created a stable inflation, and thus growth and rate environment for a long time.

But, as we know, inflation can throw a major spanner in the works, upsetting growth and rate forecasts. One of our key calls a year ago was that the Great Moderation is dead, and with it, the ability to forecast rates. Thus, before last October, the Fed maintained a hawkish stance, leading the markets to believe that 2024 would see no more than one or two rate cuts, if any. Lower inflation data in October, and a very dovish Dot Plot in December, led markets to price in seven cuts. Persistent inflation data thereafter shifted the Fed’s rhetoric once again, to the point where now markets are wondering if there will be any rate cuts at all.

As we said, a good forecast is the one that adjusts to the new data. And in an era of high macroeconomic volatility, that means it will likely change often. If the Fed, who is the primary stakeholder and ultimate decider of the interest rate in the world’s reserve currency, can’t get it right from the start, what’s the point of anyone else trying?

The problem is that it’s one of those situations where people have to try anyway.

Who cares about the Fed?

Often, we will hear: who cares what the Fed does? It makes sense for people to think in local terms. But money and markets are global concepts and interlinked.

A $114tn equity and a bigger bond market, as well as millions of listed and non-listed businesses around the world, depend on getting this call right. So do other central banks. The Dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and the American market the deepest and most efficient. It’s borrowing rates affect all businesses,

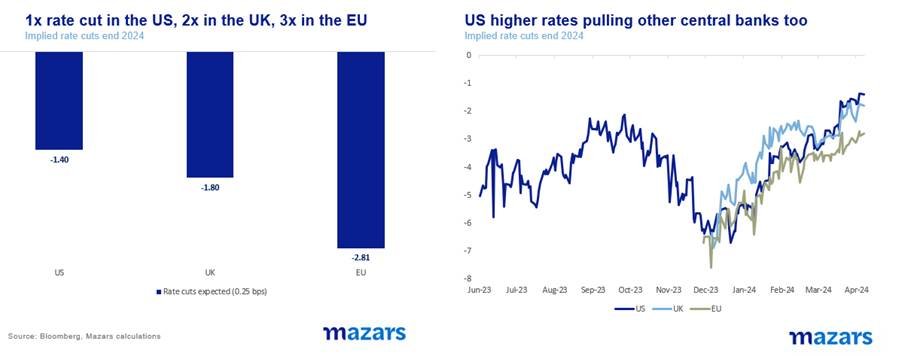

Two weeks ago, at the IMF meeting in Washington, BoE’s Andrew Bailey and Kristine Lagarde both suggested that the UK and the EU are well on their way to cut rates this year, despite the Fed’s qualms.

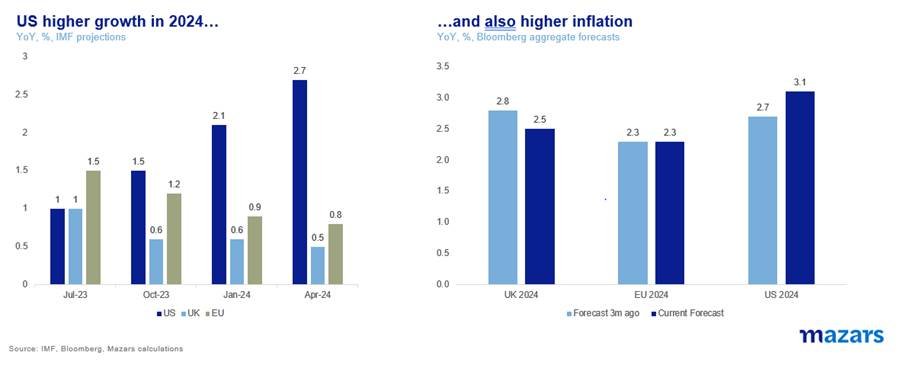

This makes sense. The European economies are projected to have less than a third of the US growth, mostly fuelled by debt and private credit, and less inflation by the end of the year.

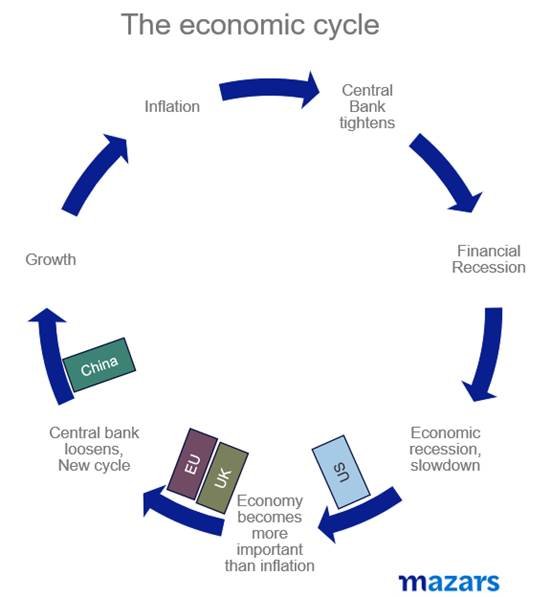

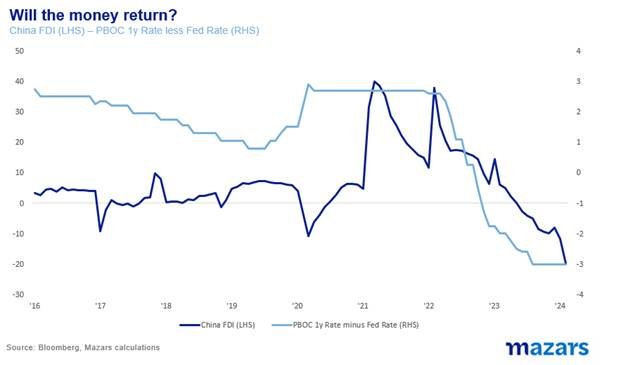

But neither the BoE nor the ECB can lower rates too much, even if they have room to, as long as the Fed holds its rates “higher for longer” for fear of significant capital outflows. Just look at what happened to Chinese FDI, when the rate differential between the Fed and the PBoC grew too big.

When you own the world’s reserve currency, a high rate is an easy way to attract foreign money. While a more expensive currency could have an effect on US exports, it’s good to remember that America is not an export-led economy. At 11% of GDP, the US ranks 140th out of 149 countries measured by the World bank in terms of export reliance, and dead last versus its major economic partners. With exports not a major concern, American policymakers might welcome a lower cost of imports.

Since 2016, throughout two different administrations and thus quite possibly a third, the US has been prioritising domestic growth at all costs. Higher growth, at a time of higher and unpredictable inflation, brings with it higher interest rates. And this compels America’s trade partners to maintain higher rates, even if they don’t necessarily want to.

What does this all mean for investors?

Uncertainty over when rates will come down seems to affect equities less and bonds more. By and large, the equity market has decoupled with either the Fed’s Balance sheet or rate announcements and focuses more on earnings and technology’s potential in the era of Artificial Intelligence. But equities can’t ignore rates forever. Over the longer term, persistently higher borrowing costs are going to erode the quality of leveraged balance sheets, first for smaller capitalisation and gradually for higher.

Meanwhile, the bond market necessarily focuses on the duration trade, which now is a higher risk one. Conservative investors might shy away from higher duration, whereas aggressive investors, and those with the patience and liquidity to way, could be willing to take on more risk.

While our cardinal rule has been and shall remain, that we “don’t fight the Fed”, we now know that “forward guidance”, be it through the Dot Plot or statements, is less potent than before. In other words, the Fed’s prediction on rates and inflation is possibly as good as anyone else’s in the market. This creates a world of opportunity but also necessitates money managers to focus on risk.