The world has moved on from the coronavirus pandemic - except for China. As President Xi embarks on his third term, he stays resolute to the ‘Zero-Covid’ policy. Some of the country’s largest cities like Guangzhou are placed under restrictions, and millions are spent on swabbing tests and resources utilized to trace individual cases one after another.

At the beginning of 2022, it is understood that President Xi’s goal is to expand China’s economy at a rate of around 5%. But underlying trends such as aging demographics, heavy debt and declining productivity growth meant such a target was a tough order to fulfill. The final nail in the coffin was the latest wave of lockdowns which confined industrial houses and warehouses, limit factory production, deferred sales and purchase activities in major provinces for prolonged periods. Local governments have been overburdened by the costs of pandemic prevention and are running out of cash. By one estimate, from Joerg Wuttke, the president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, the bill for a single round of city-wide testing in Shanghai was about $30 million.

The intention of this topic is to examine and dissect how a series of mishaps : one messy invasion, a plethora of Western sanctions and China’s fervent commitment towards ‘Zero-Covid’, took a serious toll on world trade. Typically, during this time of year, container shipment surges from “the world’s factory” - China to match the festive season demands in other parts of the world, mainly - America and Europe who are experiencing record inflation rates this year. Chinese producers are finding it difficult to produce amid labor shortages, restricted road transport and muted economic activities. Manufacturers are struggling with inventory stockpiling and exporters are receiving fewer orders. The collapse can be witnessed in the spot box rates.

Meantime, the Baltic Dry Index, which tracks the cost of transporting dry bulk commodities is bearing the brunt. The BDI that touched the 5,600 level in Oct 2021 has witnessed a downfall of 66% in 12 months’ time to 1900 levels during the same time this year (refer to graph below).

The Good News: China’s economy has rebounded at a fasterthan-expected pace in the third quarter, indicated by official figures. China's economic growth rate rebounded to 3.9% on the year in the Q3 ended September, beating a meager growth rate of 0.4% in Q2 ended June. Although the announcement followed the key Communist Party Congress meeting in October, this will not bring back the lost ground in the dry bulk market any earlier than Q2-2023, we believe.

Reportedly, the country has eased its tough restrictions even as the nationwide cases follow an upward trend. Easing restrictions, reducing congestion, availability of labor, and an uptick in industrial activities have been adding to the momentum gradually, but the overall corrections will take a little while to reflect on the market sentiments.

Iron ore: China is the world’s largest producer of steel. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China's daily crude steel output in September was about 7% higher in the month to 87 MT and 17.6% higher on the year. However, the overall production in the nine months registered a negative growth of 3.4% to 780.8 MT.

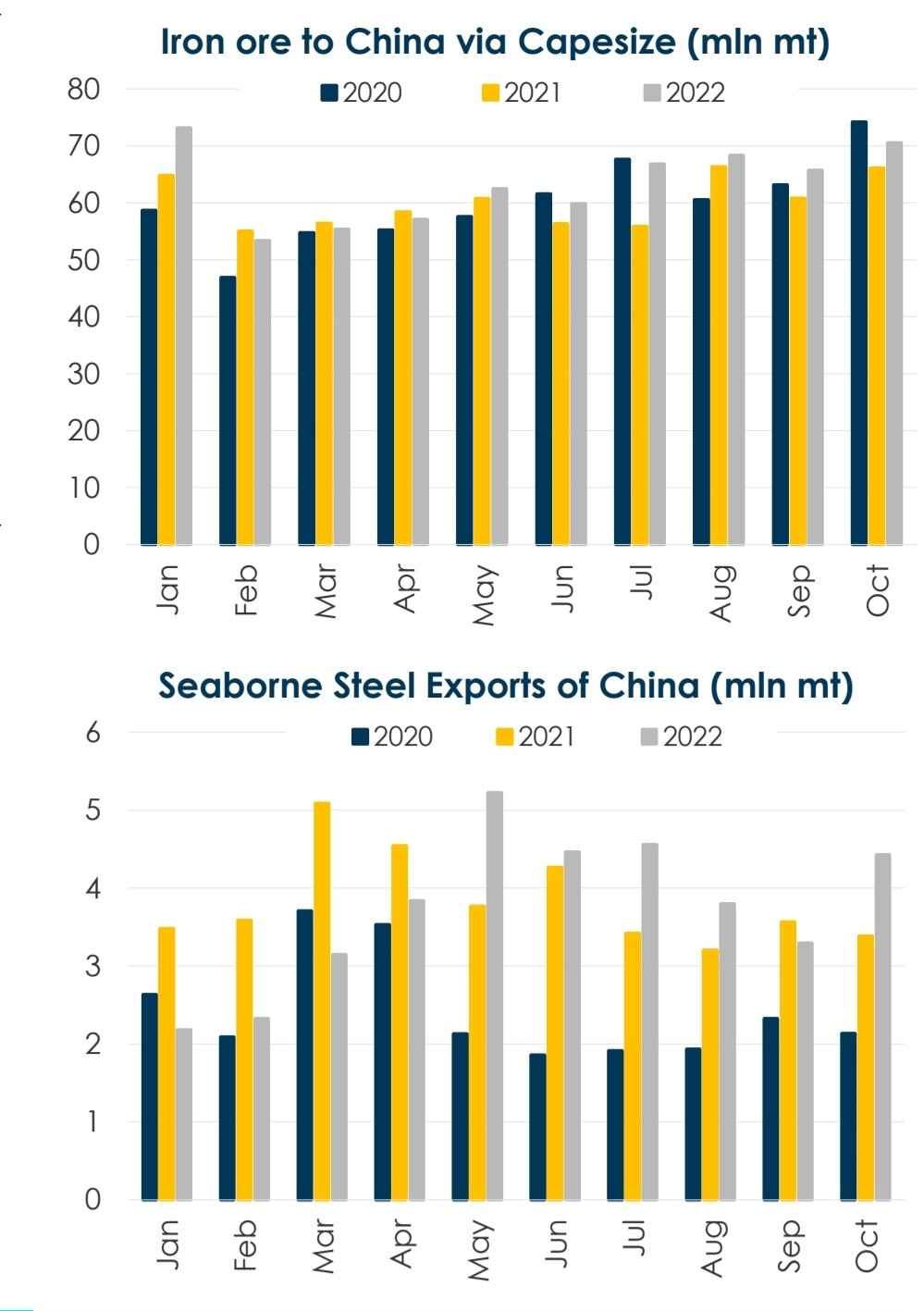

Despite that, stronger seaborne iron ore imports (via Capesize) in the month of October signal a potentially better trajectory to end of 2022.

Steel: Poor profit margins and government policy have forced steel mills to trim production while new capacity additions has kept the ball rolling. This meant that China's debt-laden property sector (which accounts for about 70% of the steel consumption) and sluggish domestic consumption are unlikely to absorb any incremental increase in domestic supply which will need to find new export markets. This can be clearly seen in the bottom right graph of the previous page, which indicates that monthly seaborne steel exports from China have been significantly higher than last year since the month of May till date.

Coal: Electricity demand in China had been impacted by the lockdowns, and the deflationary pressure was felt in the coal import figures in the first half of the current year. This is because the loss in thermal power generation was offset by renewables. China’s coal imports in the first half of the year fell 33% to 96.7 MT from 143.4 MT during the same time a year ago, reflected by the data from AXS below.

Although volumes picked up from Q3-22 onwards, the total quantity imported in the ten months is still down by 22% to 195 MT from 249 MT in the year earlier. The shipments in Q3 soared as severe drought and heatwave hit western and southern China in late July. Consequently, thermal plants geared up production to meet the spiking demand for air conditioning amid the supply gap from hydropower stations.

As data suggests, coal imports in October registered the highest quantity of 27 MT in the whole year 2022. This is because thermal plants in China typically start to build inventory in October for the heating season. This resulted in the average coal stocks at major utilities reaching a level equivalent to 25 days of use in late October, according to the China Electricity Council.

Coal imports in the rest of the months this year will remain prominent as demand for power will now pick up for two reasons – first, cold weather, and second, improved demand from industrial houses after easing its ‘Zero-Covid’ policy restrictions.

Having said so, the uncertainty remains with a price as a stronger dollar is making imported coal more expensive for the buyers, impacting the books of accounts of these power plants. Well, it is understood from known sources that China has picked up purchases from Russia at a discounted rate after Europe suspended purchasing from the country. Therefore, it is more likely that China, instead of importing through sea-route from the overseas coal market, will rely on its traditional supplier Mongolia followed by Russia via rail route.

Casting our eyes to 2023, there are certainly expectations that China will unveil a major stimulus plan after the communist party meeting to offset economic hits from lockdowns and the real estate crisis. Even if it does, there is no clarity in terms of magnitude and effectiveness and as to how long will it take for the country to implement the changes. With real estate, stock and renminbin yuan which constitute the three major components of a middle-class Chinese citizen’s total net worth being in freefall for the past year, whether the appetite or confidence for future investment or consumption.

All in all, the policymakers in China are clearly prioritizing getting Covid under control over improving the economy. That’s even considering Beijing recently releasing a list of 20 measures to refine its Covid-19 policy, laying out changes that could be interpreted as a relaxation of its rules.

In our view, until we see the complete removal of the

Three-colour “health code”, serving as an entrance pass to workplaces, restaurants, transport and most public buildings,

Mandatory routine mass PCR testing and

New quarantine facilities across the whole country (not just piecemeal interventions), it will be premature to call an end to the ‘Zero-Covid’ policy which could easily be reimposed if political agendas necessitate the need for it down the road. However, as of this point, any attempts (even without concrete details) will be magnified by every Chinawatcher as a right step forward.

Overall, this means although relaxed (in relative terms), Covid-related disruptions will likely persist around the efficacy of Chinese vaccines and will challenge revival in the economic activities over the next year. In fact, conflicting messages might introduce more confusion. For example, on last Monday, a rumour took hold that Shijiazhuang, a small city 260km from Beijing, was to become a test case for China’s reopening, But rather than feelings of elation and relief, it was reported that the speculation was met with alarm by most in the city of 11 million.

This unfortunately highlights one of the key barricades to China joining the rest of the world in living with Covid-19: a fear of the virus. Since 2020, the government and local authorities had repeatedly emphasized to its people that Covid-19 was so vicious that the country needed to be closed off to combat it. In fact, the ability to enforce such measures was touted by Chinese leaders as China’s unique political advantage over its Western peers. Clearly, adjustment will require more than just a rhetoric shift and a 180-degree flip in mindset.