By Ulf Bergman

The year has started with a significant disruption of the global seaborne coal market, with the world’s largest exporter effectively banning all shipments of the commodity to foreign destinations during January. The move by the Indonesian government followed increasing concerns that the low supplies at many domestic power plants could lead to widespread blackouts. It also highlights a rising tendency for Indonesia, under President Joko Widodo, to exert greater control over its natural resources and move the nation further up on the international value chain.

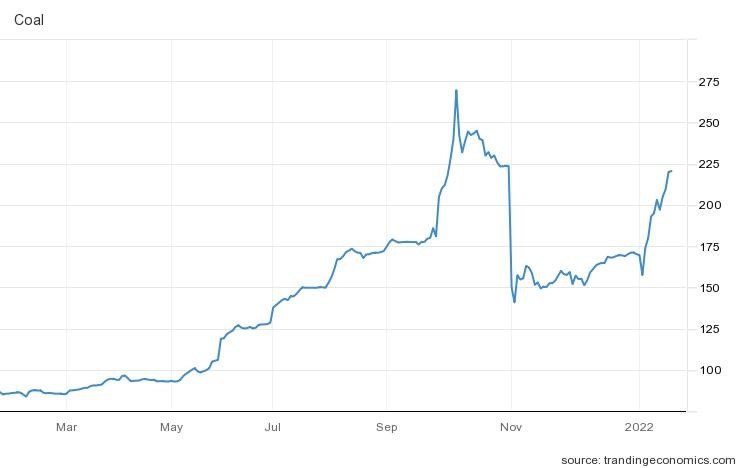

The clampdown on exports has sent coal prices sharply higher, after two months on relatively modest levels following China’s move to cap domestic prices. Newcastle coal futures have gained around forty per cent during the month to date and are currently trading just above 220 dollars per tonne. Despite the recent surge, prices are still around twenty per cent below the peak reached in early October last year.

Newcastle Coal Futures – USD per tonne

However, the effect of the export restrictions has been somewhat blunted by the continued high coal production in China, the world’s largest consumer of the commodity. In the wake of the squeeze on energy supplies that emerged during the second half of last year, the Chinese leadership lifted previous output restrictions and called on miners to maximise production. As a result, output in December reached a record 385 million tonnes, and annual production rose by almost five per cent to just over four billion tonnes. The expanded production has also translated into new seasonal highs for thermal coal inventories at the nation’s essential power plants, with quantities large enough to cover three weeks of power generation. Nevertheless, the Chinese authorities have instructed the miners to maintain normal production levels over the Lunar New Year holiday, as the supplies from the nation’s largest overseas provider have become restricted. In addition, power consumption is expected to continue to grow at a robust rate after last year’s ten per cent expansion.

While China, for now at least, has been able to escape the worst of the fallout of the Indonesian coal export embargo, other countries are more dependent on regular imported supplies. Japan, South Korea and the Philipines have all vented their disapproval of Jakarta’s initiative. They fear it can cause rising inflation and other economic disruptions and have urged a rapid policy reversal.

So far, the export ban has not been total, with a limited number of vessels allowed to leave with their coal cargoes. However, congestion in and around the Indonesian ports remain elevated, with average waiting times rising rapidly. For Panamaxes, the dominant tonnage segment for the Indonesian coal trade, average waiting times have doubled to fifteen days since the beginning of the year, according to data from Oceanbolt. While the number of Panamaxes held up in the congestion around the Indonesian islands has declined to 113 vessels in recent days, it is still almost twice as many as when the export ban was announced.

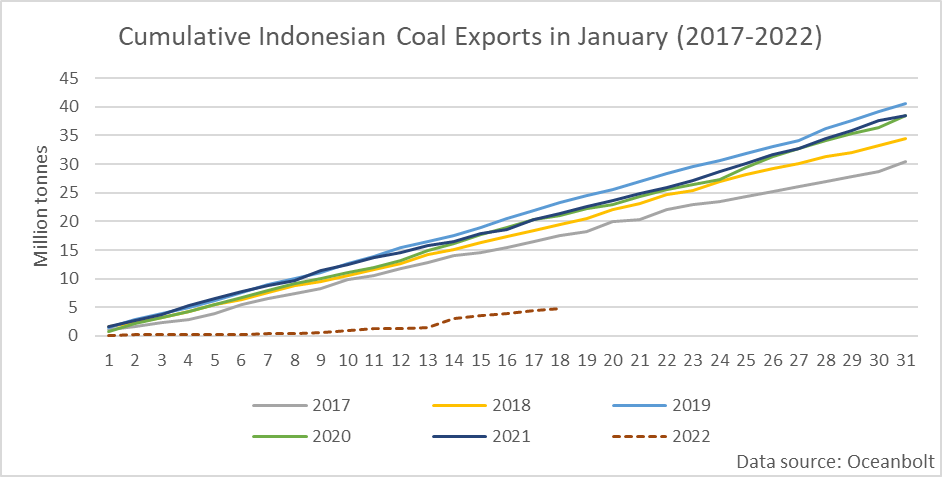

Despite some vessels having been allowed to leave, shipped volumes are still a far cry from normal levels. According to data from cargo tracking platform Oceanbolt, 4.8 million tonnes, a quarter of the average volumes over the previous five years, has been loaded onto vessels during the first eighteen days of January. However, it is essential to remember that loaded does not necessarily mean departed. Many ships are still awaiting permission to leave, and, hence, the actual exports are likely to be lower.

The drop in Indonesian coal exports has yet to translate into increasing volumes shipped from alternative sources. Among the rest of the top five exporters, month to date shipments have remained below the average for the last five years. The lack of substitution effects suggests that most Asian buyers were taken by surprise by the new Indonesian policy and are hoping that the ban will only be in place for a short period of time. A shift to alternative sources would, in many cases, mean longer distances for the cargoes and would therefore not solve any immediate demand shortages.

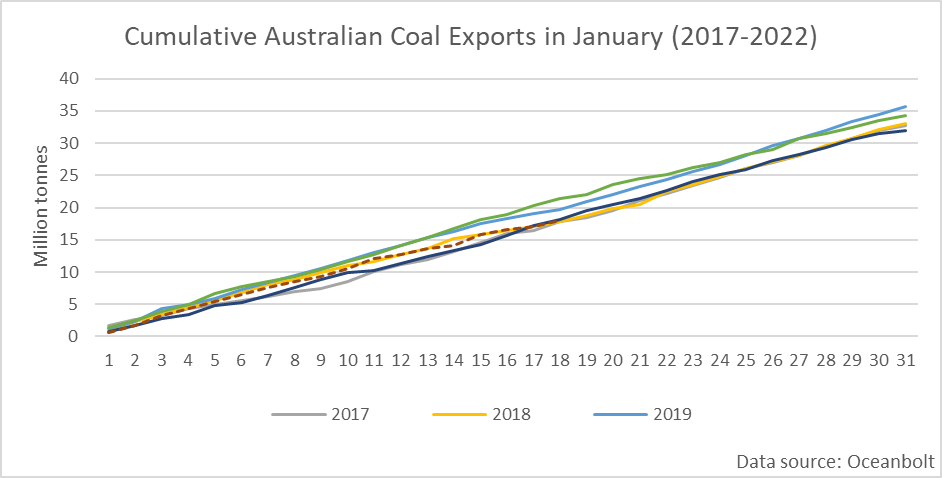

Since China imposed an import ban on Australian coal in late 2020, volumes from the world’s second-largest exporter of seaborne coal have remained subdued. So far this year, shipments from Australian ports are in line with the same period in 2021 and are ten to fifteen per cent below the levels seen in the years immediately prior to the Chinese ban. Hence, suggesting that, should the Indonesian export restrictions remain in place for longer than expected, Asian buyers may increase

their purchases from Australia.

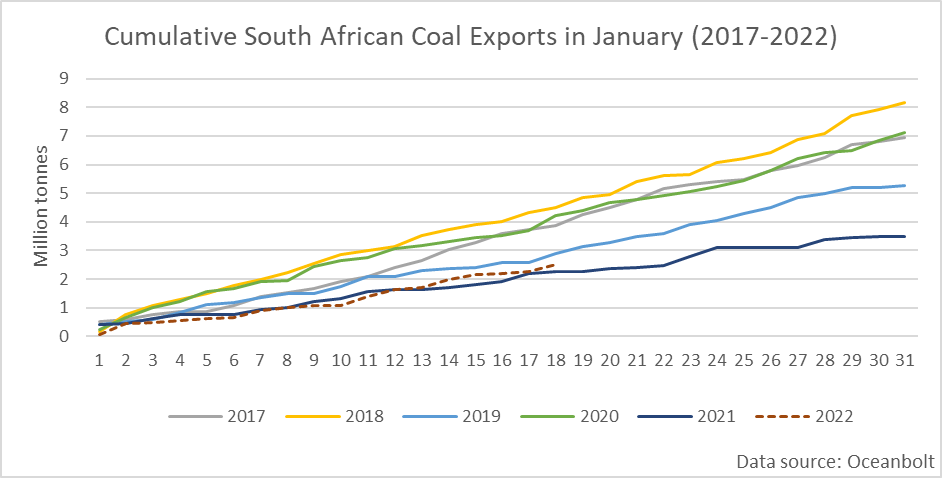

South African coal exports have not recovered from the impact the pandemic had on mining operations, with volumes approximately 35 per cent below the pre-pandemic average. During the first three weeks of January, shipments were marginally above last year’s reduced volumes but some two million tonnes below the record set in 2018.

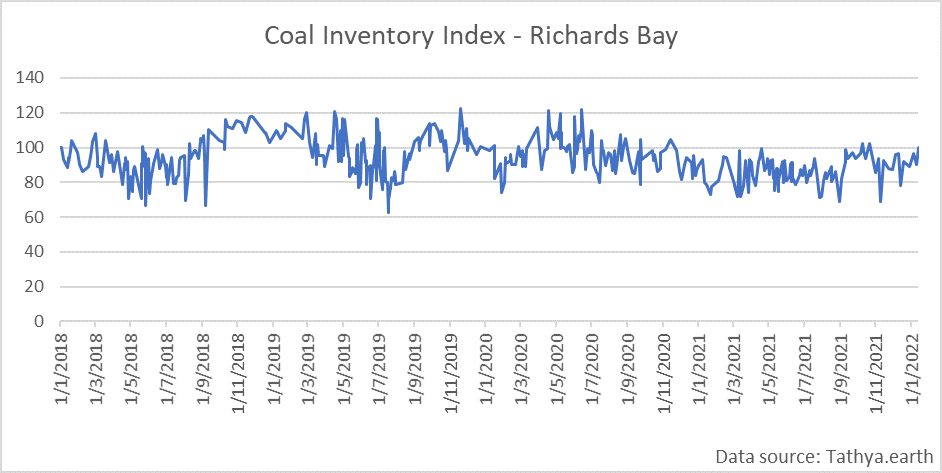

However, Portside inventory levels in South Africa’s main export port, Richards Bay, have been showing signs of a recovery in recent weeks. According to satellite data from Tahtya, stockpiles are near the highest seen since the latter parts of 2020 after trending lower for much of last year. The rebound could indicate that South African coal exports will increase in the coming months.

With the exception of cargoes coming from Russia’s far-eastern ports, any major shift in Asian flows of seaborne coal due to the Indonesian export ban will increase the tonne-mile demand as longer distances need to be covered. However, at this stage, a wait-and-see approach appears to be the preferred course of action, with many utilities hoping that diplomatic pressures on Indonesia will ensure that the ban becomes short-lived.