Week ahead

Last week saw the second-worst opening to the year for US equities post-Lehman, prompted by a hawkish Fed and led by a decline in highly valued US tech stocks. This week is expected to provide the definitive test for the world’s most prominent sector and possibly set the tone for the next few months.

Meanwhile, the earnings season has begun in the US, with banks reporting throughout the week. Analysts will probably pay less attention to Q4 numbers and more to the outlooks of companies, especially those with complicated supply chains. Chinese and US inflation numbers should test the central banks’ strategy, especially if US price rises cross the critical 7% threshold. A key US consumer survey at the end of the week should show exactly whether the impact of higher prices is further worsening consumer sentiment.

Finally, as inflation is gripping the world, it will be interesting to watch a speech by Christine Lagarde on the 14th. The ECB has been notably more dovish than the Fed and the Bank of England, mainly because of lower-wage pressures in the continent. However, the ECB chair is coming under increasing pressure, especially from inflation-sensitive Germany, to end QE sooner and raise the cost of money.

Lack of normality means lack of visibility

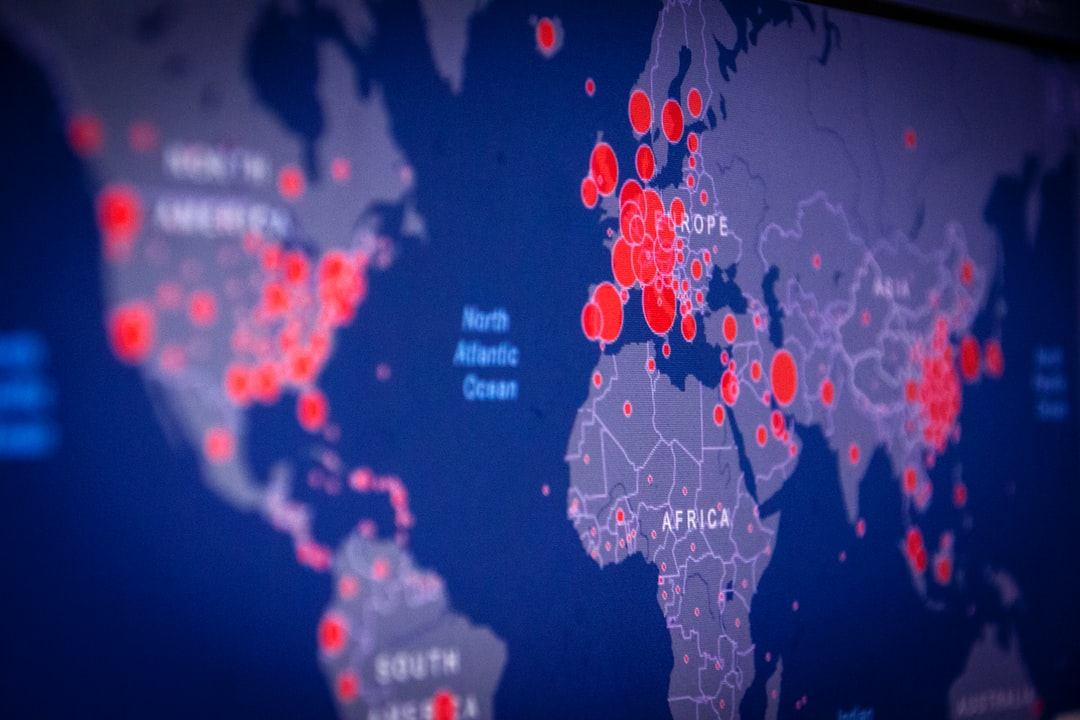

As we enter the third year of the pandemic, it is becoming increasingly apparent that aggregate economic performance will, once again, be largely dependent on the evolution of Covid-19. Economic performance doesn’t just boil down to GDP. Employment metrics are equally important, as is inflation, a key determinant of financial market activity, especially now that QE is truly taking a back seat for the first time in twelve years.

Outlooks come during a particular time in the year, particularly the last couple of months. Investment professionals are asked to give their predictions for the global economy and stock markets and, in the interest of providing a modicum of certainty, they do.

However, an element that’s habitually missing from these forecasts is the degree of certainty. As long as the pandemic remains unpredictable, economic visibility will be exceptionally low, and with it, forecast certainty.

Too often we hear predictions about how Omicron will speed up the end of the pandemic. It might very well be the case, but no one can account for the emergence of new dominant variants, especially with the current infection rates.

We can’t allow ourselves to fall into the trap of trying to predict the timeline for an endgame when the next turn is unknown. Currently, risk is non-linear, but parabolic. All it takes is one new vaccine-resistant dominant variant to undo months of global vaccination and throw predictions out of the window.

In finance, parabolic risk is dealt with unfettered money printing. In real life, there is no such thing as central bank assurance. Vaccines can be physically produced and distributed at certain rates. Parabolic risk is notoriously difficult and sometimes impossible to calculate, and degree of certainty is low at any rate.

Thus, we intend to consider Omicron, and any other deviation from the path towards normality (whatever the ‘new normal’ looks like) as reason for caution, because it breeds further uncertainty for government and business decision-makers.

If questions like ‘when is the pandemic going to end’ are unanswerable, we need to ask different questions: Will global policymakers work together to bring a swifter end to the pandemic? Will that even make a difference? Will companies switch business and logistics models to account for a ‘forever virus’ strategy? Is there a breakpoint for this to happen? These are the questions we should focus on for the next few months.

Meanwhile, we have to acknowledge that lack of central coordination means that pandemic-induced change is bottom up. The state of the world is currently a Jackson Pollock painting.

Whatever new world emerges will not be the predictable outcome of one policy but the unpredictable net force of thousands of different policy and business responses. Focusing on individual problems still tells us nothing about the final general picture.

We know very little about how inflation will develop, or the pandemic or how supply chains will respond. Up until a few months ago, at least we knew the central driver for risk assets: central bank accommodation. However, inflation has, at least for now, de-fanged central bankers.

Here’s what we do know: US stocks are expensive and concentrated but there aren’t many alternatives to the world’s deepest and most advanced market. In fact, there are few alternatives to stocks altogether, in a world where inflation might ‘eat’ 5% from cash and bond yields each year.

In fact, fixed income is universally expensive and central banks might not be able to keep buying new issuance at the current pace. An asset re-rating (vernacular for a correction in asset prices) is increasingly possible due to the QE paradigm shift.

Meanwhile, inflation is here, now. All that uncertainty is bad for business. But how risk assets are going to do is still unknown, as the drivers have been for too long completely decoupled from all of the above. It could be that the ‘residual liquidity’ and ‘There is no alternative to stocks’ arguments prevail. Or it could be that markets go into ‘fear mode’ and secular volatility rises.

In hindsight it will all make sense, it usually does. But from where we are today, we feel that the unprecedented uncertainty mandates less tactical and more strategic positioning.

In a post-QE world, where ‘beta’ strategies will be less important and ‘alpha’ strategies have low conviction, it’s a good idea to stick to ‘first principles’. Trust long-term assumptions and strategic asset allocation as a main driver of portfolio performance. Portfolio weights, such as our fixed income and duration underweight, should reflect only high conviction.

The key takeaway from our predicament should be a sobering one: Humanity’s innate anthropocentrism* and technological prowess must not lead to the false conclusion that nature has been, or may yet be, conquered. A simple virus can upset civilisation as we know it.

So what does this say about much bigger threats like climate change? Environmental preservation in the years to come, will not be an option, but a necessity. Which is why this theme will become gradually even more central to our investment approach as years go by.