By Ulf Bergman

At the same time as the dark clouds are gathering above the horizon for Chinese manufacturing and steel production, India is facing rapidly depleting stockpiles of coal. An industrial recovery, following the easing of restrictions in the wake of falling Covid infections, has fueled a surge in demand for electricity. Coal-fired power production has been widely employed to satisfy the growth in demand. In August, power generation increased by over sixteen per cent compared to the same month last year and was almost three per cent above the levels in July. However, coal-fired power production last month rose by 23.7 per cent year-on-year and by over four per cent month-on-month. The increasing demand for coal has led to concerns of an imminent shortage, as inventories are critically low at many power plants. According to India’s Central Electricity Authority, there are already a limited number of plants that have run out of stocks and close to 200 plants have less than a week’s supplies available.

Notwithstanding an ambition to increase the use of renewable energy, coal-powered plants remain the dominant source of electricity in India at 70 per cent. Three-quarters of the coal consumed in the country is also used for generating electricity. The output from coal-fired power plants has risen faster this year than the growth in renewable energy generation. During the first eight months of the year, coal-fired electricity generation grew by almost twenty per cent and beating the fifteen per cent growth in renewable energy.

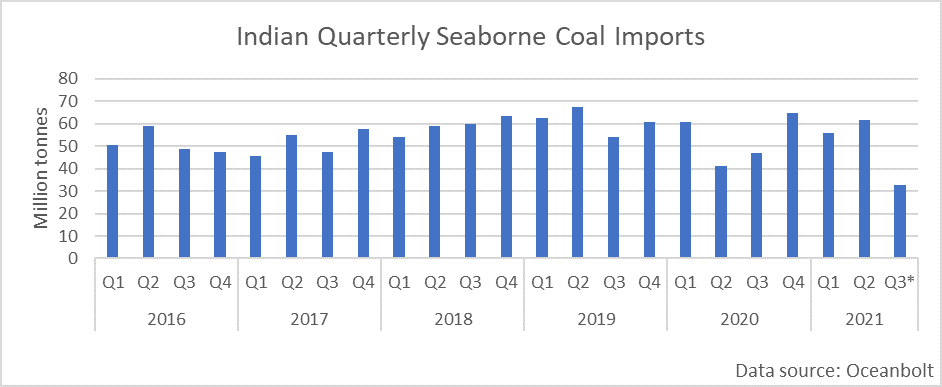

Despite the country being home to the fourth-largest coal deposits in the world, India has to import a considerable amount to cover its demand. It is the world’s second-largest importer of the commodity, behind China, with approximately 245 million tonnes being discharged in Indian ports during the pre-pandemic peak in 2019. So far this year, 150 million tonnes of seaborne coal has found its way to Indian ports which may not imply a new record year. However, Indian coal imports often increase during the latter part of the calendar year. In addition, the authorities have asked the utilities to increase imports to alleviate the developing supply squeeze, which runs contrary to recent attempts by the Indian government to reduce overseas coal purchases.

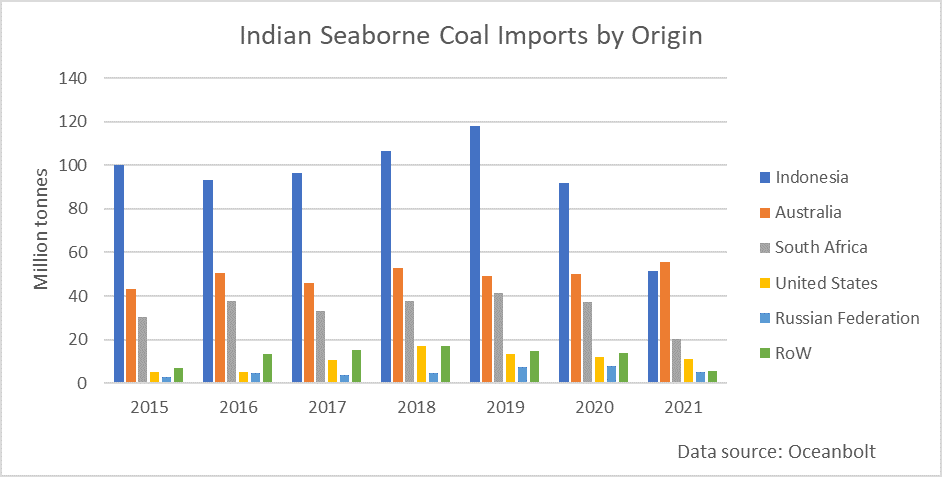

It has been highlighted in Ocean Analytics’ previous Insights contributions that the ongoing diplomatic tensions between China and Australia have seen large parts of the Australian coal exports being diverted to India following the Chinese import embargo. This trend has remained in place throughout the year and the Australian miners have usurped the top spot previously held by the Indonesian suppliers. The news that India is likely to increase the import of coal is likely to delight the Australian coal miners, who can hope to ship an even greater part of the coal they previously dispatched to China. During the first eight months of the year, India has already imported more coal from down under than it did in a whole year previously. At the same time, Indonesia has lost its previously dominant position in the Indian market but much of its output is now going to China instead and is replacing the banned Australian imports.

South Africa has long been the third-largest source of imported coal for the Indian marketplace, with annual volumes averaging 37 million tonnes in recent years. The country’s share of the seaborne imports has also remained stable during the years leading up to the pandemic, but as the Covid related challenges increased during this year the market share has declined. This has been even more pronounced in the last few months with civil unrest affecting the region around Richards Bay, where the country’s largest coal port is located. While cargo operations have resumed in the wake of the violent protests, volumes shipped from the port in August were fifteen per cent below the same month last year, according to data from Oceanbolt.

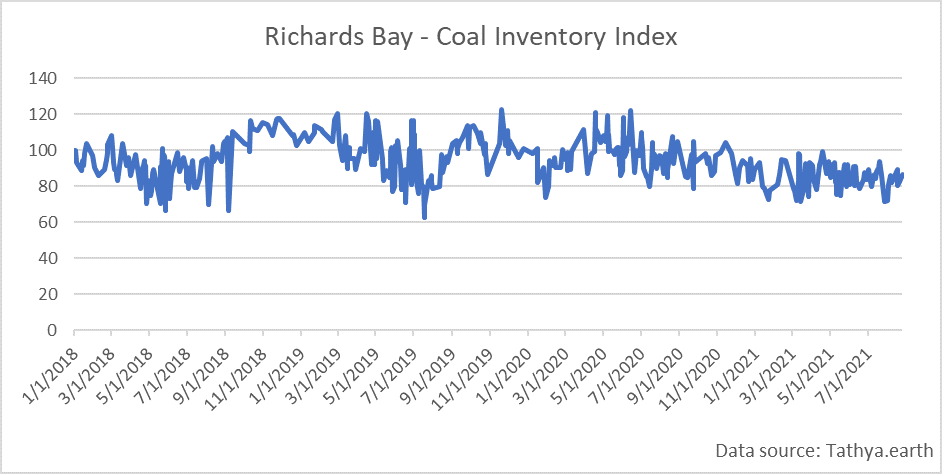

The unrest affected the rail lines serving Richards Bay, reducing the amount of coal that reached the port and depleted stocks. According to data from Tathya.earth, coal inventories in the port have recovered somewhat since the immediate aftermath of the riots. However, the stockpiles remain below average and have also seen a negative trend in recent months. This would suggest that South Africa is unlikely to, at least in the short term, cater to the increasing Indian coal demand. While Indonesian export volumes to India remain well below what has been provided in the past, China’s continued robust demand for imported coal implies that the additional volumes available for the Indian market could be limited. Hence, leaving Australia as the main contender to meet the increasing Indian demand for coal.