By Ulf Bergman

On the back of an escalating energy crisis in Europe, coal prices in the region have kept rising and have reached two hundred dollars per tonne for the first time in thirteen years. While much of Europe is committed to decarbonisation and limiting the use of coal for power production, a tight supply situation for natural gas have seen demand for the dirtier fossil fuel back in vogue. The lengthy cold conditions during last winter have left gas inventories depleted across the continent, at the same time as supplies from Norway and Russia have remained under pressure. Additionally, the lack of wind has limited the production of renewable energy. This situation has forced many European utilities to step up their coal purchases ahead of the approaching winter. The growing demand for thermal coal from power plants has also depleted stockpiles in the European ports to the lowest levels, for this time of the year, since 2016. Global coal production has also been affected by adverse weather conditions and pandemic related production disruptions, adding to the upward pressure on prices.

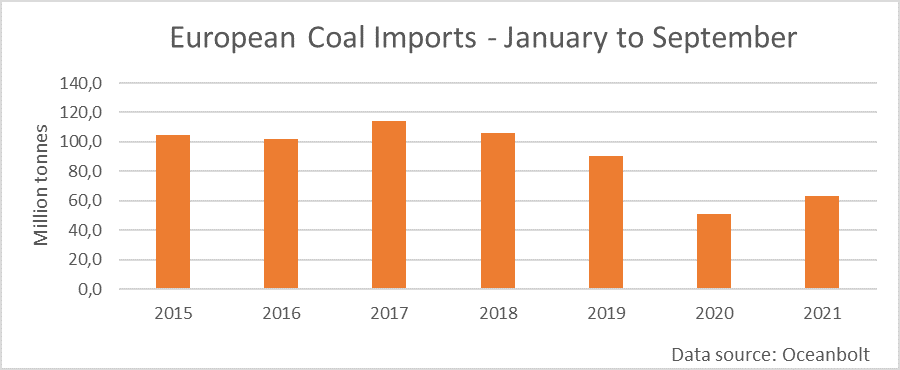

With only a few days remaining of the month, European seaborne imports of coal are on track for reaching 7.5 million tonnes in September. While still below the pre-pandemic levels of 2019, it will be forty per cent above the same month last year and around five per cent more than seen in August. With the European energy crisis brewing in recent months and driving seaborne imports higher, the volumes of the first three-quarters of the year look set to be a quarter higher than last year. Much of the increase is an effect of the solid European economic recovery, with the previous year’s drop being a bit of an outlier as the continent faced extensive restrictions. The higher imports are nevertheless likely to be seen as a policy failure in many quarters.

As European seaborne coal import volumes have recovered lost ground, the nature of the trade has also changed. After seeing its importance eroding since 2017, the Capesize segment has seen a revival this year and more than doubled its market share in the last year. At the same time, more and more Australian coal has found its way to European ports. Russia remains the dominant player in the European market. Still, the Australian market share has increased as the diplomatic ruckus with China is forcing it to find alternative customers, adding a healthy amount of tonne-mile demand to the trade.

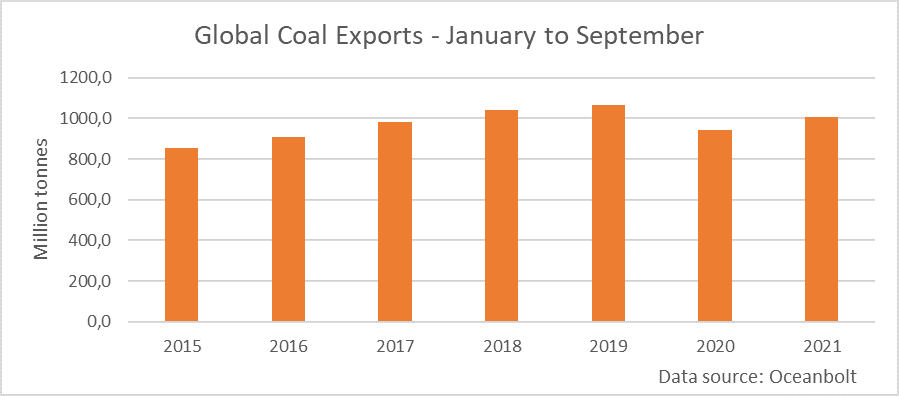

The rebound in the seaborne coal trade is by no means solely focused on Europe. The shortage and subsequent price rally for natural gas have forced many countries to increase their reliance on coal, either because of supply constraints or economic reasons. Global seaborne coal exports have therefore recovered since last year’s dip. The volumes shipped during the first nine months of the year have grown by approximately seven per cent year-on-year, assuming the remaining days of the quarter are behaving as predicted. However, total export volumes are still around four per cent below the pre-pandemic peak.

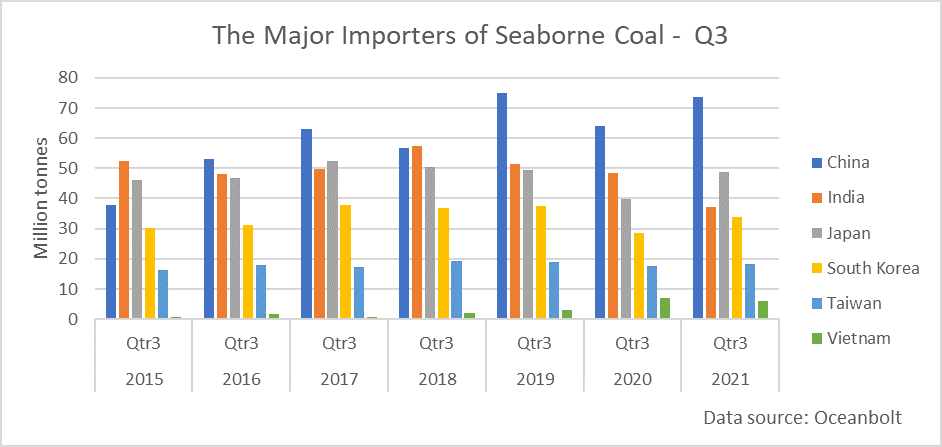

The aggregate data for the rebound of the global coal trade obscures that the recovery is not homogenous among the major importers. India is the notable exception from the year-on-year growth in the third quarter among the six largest importers. Despite reports that Indian coal inventories are at critically low levels, the country’s imports fell by ten million tonnes compared to the third quarter last year. According to the nation’s Central Electricity Authority, inventories have fallen to the lowest since November 2017 as the country’s economy has rebounded and sent electricity demand higher. Hence, India may be forced to increase its imports or face blackouts that would threaten the continued economic recovery.

The squeeze on the global supply of natural gas is unlikely to disappear anytime soon, suggesting the demand for thermal coal will remain robust. Assuming countries like Indonesia and Colombia are returning to maximum production soon, once pandemic pressures and adverse weather conditions have receded, there is also the potential for global coal shipments to increase further. However, the upside is finite as investments in new capacity has almost come to a standstill in recent years after most banks ceasing lending to the sector.