By Ulf Bergman

This week has seen some rather disappointing economic data coming out of China, which has raised fears among analysts of an imminent slowdown of the Chinese economy and fueling concerns about the continued global economic recovery. The continued struggle for the domestic Chinese economy to regain its momentum was further highlighted by weak retail sales growth, with consumers spending less than expected during the summer holiday break. The repeated coronavirus outbreaks and new travel restrictions have dented consumer confidence, resulting in the growth of expenditures at a meagre two and a half per cent and well short of the seven per cent anticipated by the economists.

Industrial production held up somewhat better than the retail sales last month. The robust demand for Chinese produced goods continues to cause congestion in container ports worldwide, most notably on the US West Coast. The 5.3 per cent manufacturing growth underscores the continued unbalanced recovery of the Chinese economy, even though it fell somewhat short of expectations. Despite keeping up better than the domestic service and retail sectors, the growth in industrial output has been on a downward trend since hitting the stratospheric levels during the early parts of the year. It has been inevitable that economic expansion rates would become less spectacular as the base effects wore off and the recovery matured. However, the extent of the retreat suggests there is a case for the Chinese central bank and government to step up their efforts to support the economy. A further cut in the reserve requirement ratio for banks, following the surprise cut in July, by the People’s Bank of China, is a likely candidate for a first move to add liquidity and support the economy. China’s National Bureau of Statistics also said in a statement when it released the data that the economic recovery “still needs to be solidified”, suggesting that additional policy initiatives are on the cards.

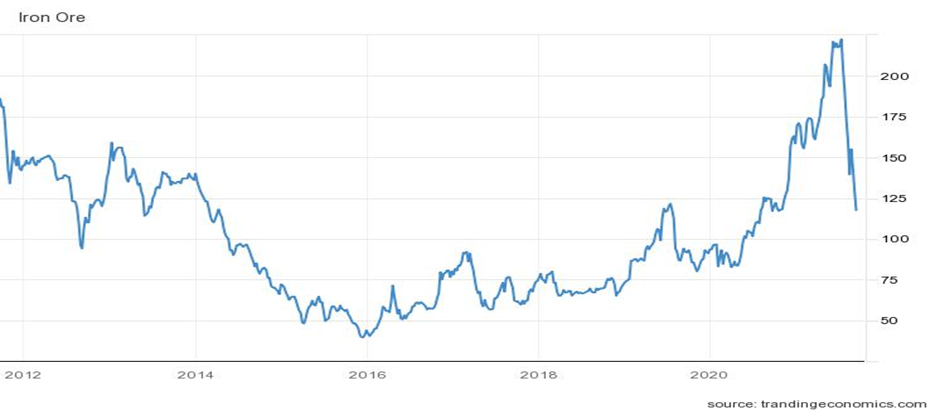

However, the sharp decline in steel production grabbed most of the headlines and is likely to cause the greatest consternation among analysts. The combined effects of Beijing’s clampdown on steel production and extensive Covid outbreaks, which have reduced construction activities and steel demand, resulted in the steel output falling by thirteen per cent last month. After the drop, the Chinese steel production is at the same level as immediately after the country exiting the first set of pandemic lockdowns in March 2020. The news contributed to iron ore prices continuing on the downward trajectory that started in the middle of July, with prices at the lowest since November last year after a drop of almost fifty per cent over two months.

Iron Ore Prices 2011-2021 (USD/tonne)

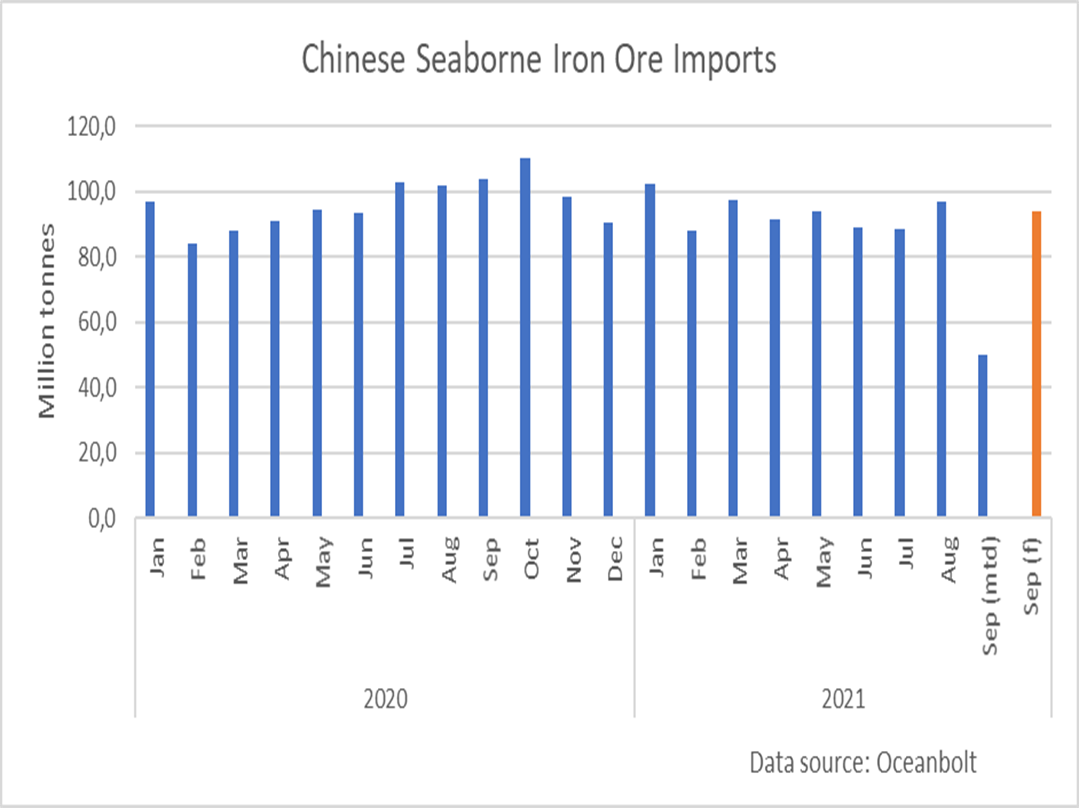

The considerable drop in steel production is yet to translate into a significant fall in seaborne imports of iron ore. According to data from Oceanbolt, volumes discharged in Chinese ports during August fell by five per cent compared to the same month last year. Notwithstanding the year-on-year decline, the iron ore flow into the Chinese ports was the highest since March. The trend of annual decline looks set to continue, following last year’s strong import growth. So far, some fifty million tonnes have shipped to Chinese ports in September, which suggests the month’s annual decline will be approximately ten per cent. Despite the drop, the volumes discharged are in line with the year’s monthly average.

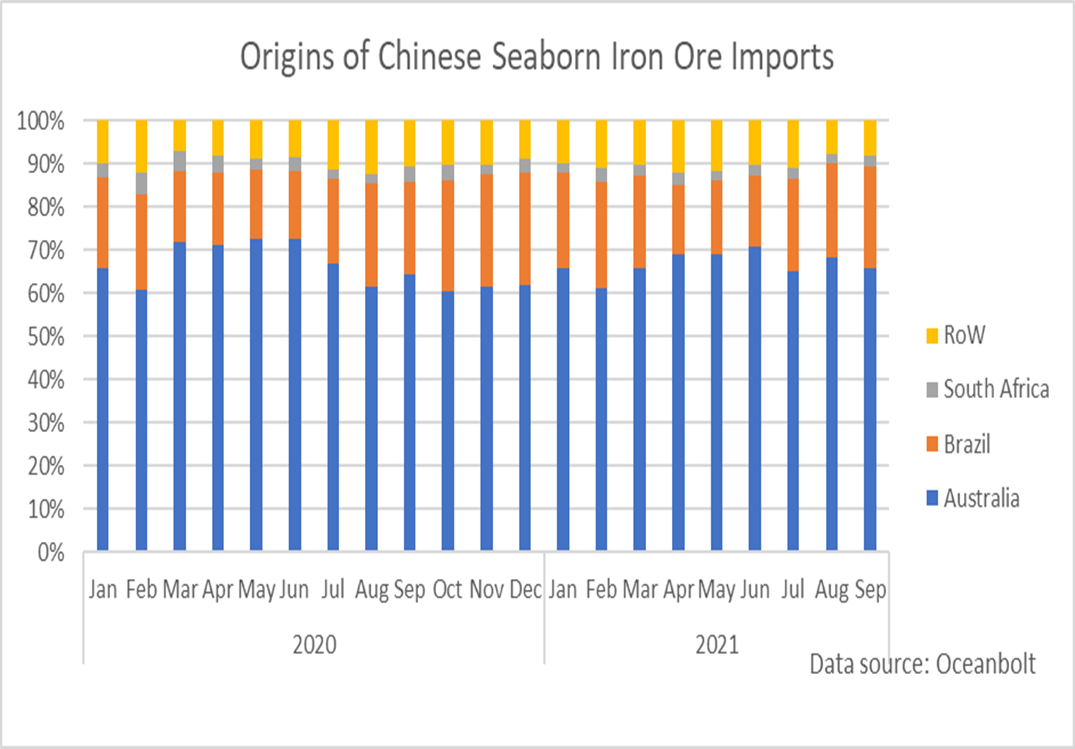

Recent months have seen Brazil increasing its Chinese iron ore market share as production has recovered. At the same time, the Australian stake has returned to its long-term average. The iron ore volumes imported from Australia have remained relatively stable despite the ongoing diplomatic friction between Beijing and Canberra. The combined market share for Australia and Brazil has also been increasing, with only ten per cent of the Chinese demand catered for by other exporters

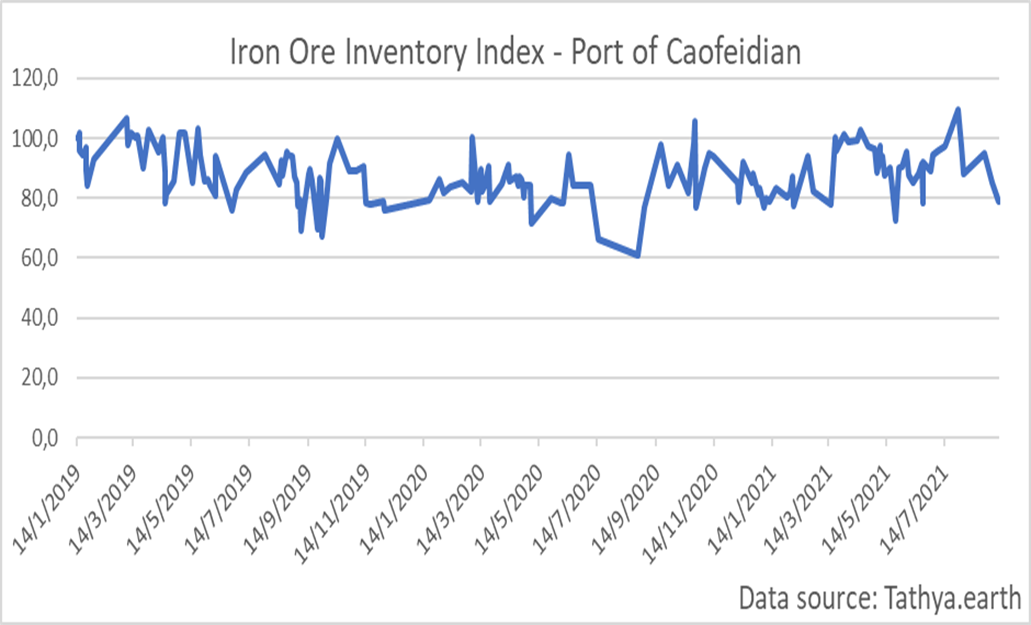

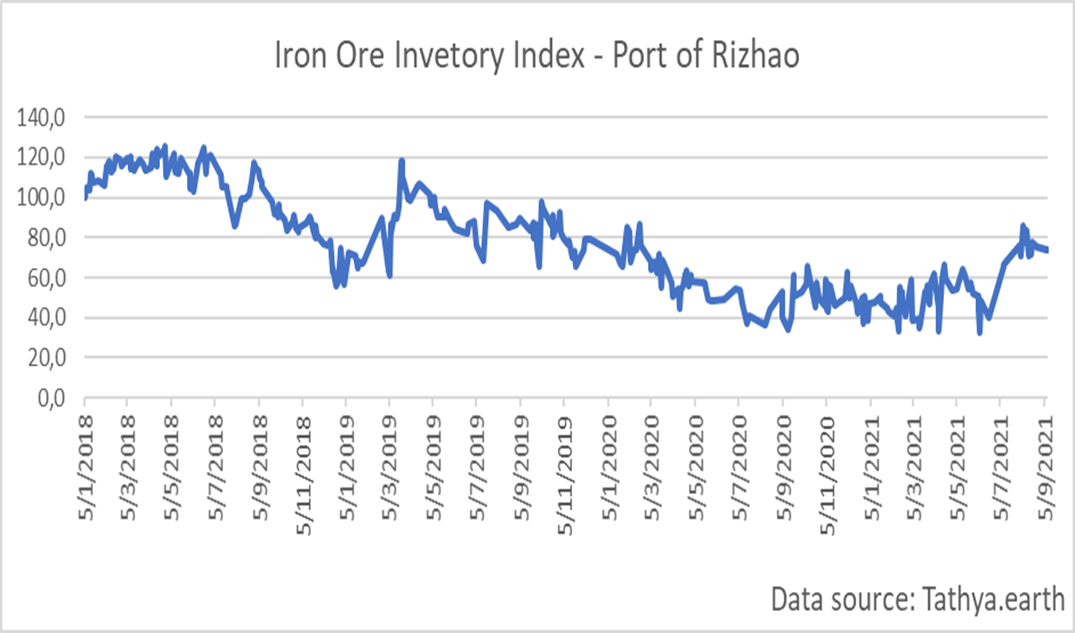

The drastic drop in Chinese steel output and somewhat less dramatic decline in iron ore imports could suggest that inventories are building up. Data from Tathya.earth highlight a mixed picture for Chinese portside stockpiles, with two of the largest iron ore ports, Caofeidian and Jingtang, seeing inventories trending downwards.

For some smaller ports, such as Rizhao and Quingdao, portside stocks have been building up during the summer, suggesting that the clampdown on steel production may have some effects on inventories. However, Mysteel has recently reported that the iron ore stockpiles of the Chinese steel mills are at a seventeen-month low, leaving room for a shift of portside stocks and complicating any analysis.

The ongoing clampdown on steel production is likely to keep Chinese iron ore imports subdued by recent standards. On the other hand, any policy measures dealing with the decelerating Chinese economy could increase demand for steel and see iron ore imports picking up again. The recent price drop by around fifty per cent is likely to make such a move more palatable for the Chinese leadership, as it will reduce the perceived wealth transfer to Australian miners.