By Ulf Bergman

There is always the risk that any analysis of the iron ore markets gets rather China-centric. However, as the country accounts for around seventy per cent of global seaborne iron ore imports, events and new policies in China will significantly impact prices and volumes. The early parts of the year suggested that China was on course for yet more annual records for iron ore imports and steel production. As Chinese steel mills consumed increasing quantities of iron ore, the prices kept rising, and the inflation alarm bells started to ring in Beijing. The Chinese authorities issued a raft of measures to bring the surging prices under control. Production quotas were put in place to ensure that the annual steel output would not exceed last year’s levels, and environmental restrictions were also used to bring steel mills to heel.

The high prices also contributed to a significant wealth transfer to Australian miners, which is likely to have galled Beijing as its diplomatic ruckus with Canberra deepened. Imports of iron ore have remained uneffaced by the import bans imposed on many Australian products, as the possibility to substitute remains limited, and any ban would be akin to economic self-harm. Hence, lower prices were politically attractive.

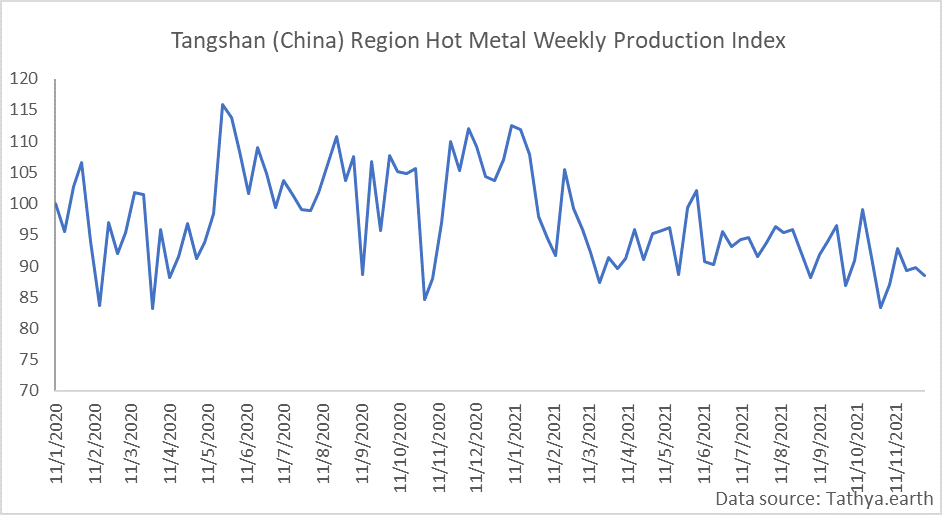

With the Winter Olympics approaching, emission control became increasingly important during the second half of the year. Beijing wants to ensure good air quality and blue skies for the games, and with the steel industry being a significant contributor to pollution levels, a clampdown was always inevitable. In addition, the travails of the Chinese property sector have weighed heavily on demand in recent months. As a result, output in one of the largest steel-producing regions, Tangshan, has been trending lower throughout the year, according to satellite data from Tathya.earth.

As discussed in a previous Ocean Analytics contribution, iron ore prices have been recovering somewhat during the past six weeks after the epic retreat from the highs recorded in May. The rebound has been fuelled by expectations of higher steel production and demand once the Olympics have passed and more stimulus to support the flagging growth rate are introduced. Also, November saw a pick up in production, as many steel mills had met their annual production cuts and were allowed to boost output.

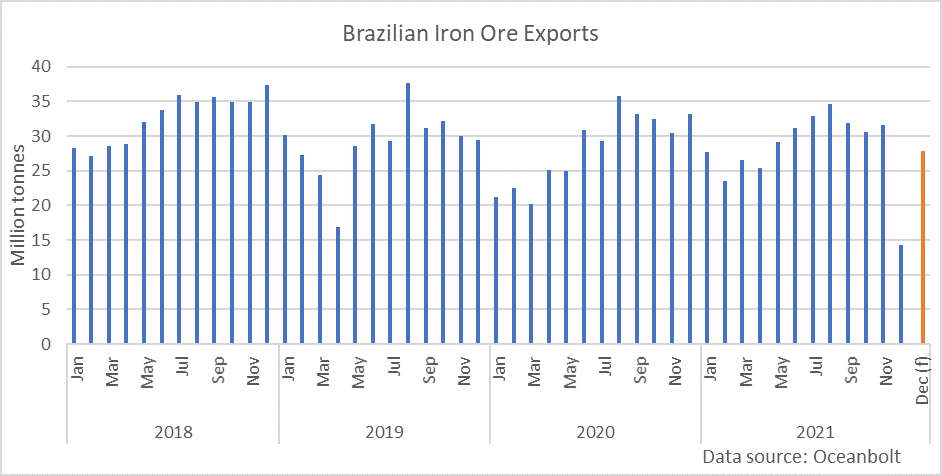

Despite China’s restrictions on steel production, global seaborne iron ore exports have held up well. According to cargo tracking data from Oceanbolt, volumes matched the pre-pandemic peak last month at 131 million tonnes. However, based on the quantities shipped during the first half of the current month, December may fail to match last year’s exports by almost five per cent. The projected decline is due to falling Brazilian export volumes, which, at 28 million tonnes, could be on track for a sixteen per cent drop compared to the same month last year. While the Brazilian full-year exports are on course to be higher than in the previous two years, the weak monthly export volumes contribute to the current year falling ten per cent short of the record set in 2018.

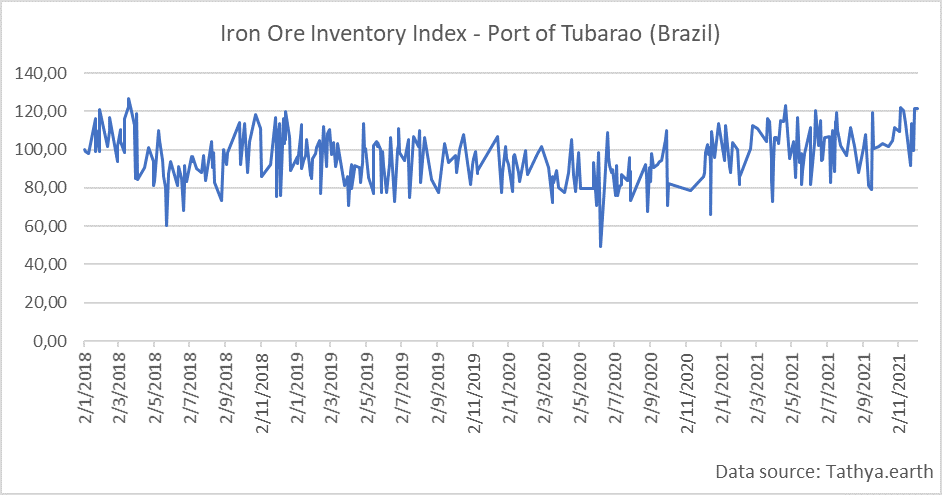

At the same time, as Brazilian export shipments are softening, iron ore inventory levels are building up in the Port of Tubarao. Recent satellite-based inventory data for Brazil’s largest port for iron ore suggest that levels are among the highest recorded in recent years. Hence, there is the chance that December’s export volumes may catch up following a sluggish start.

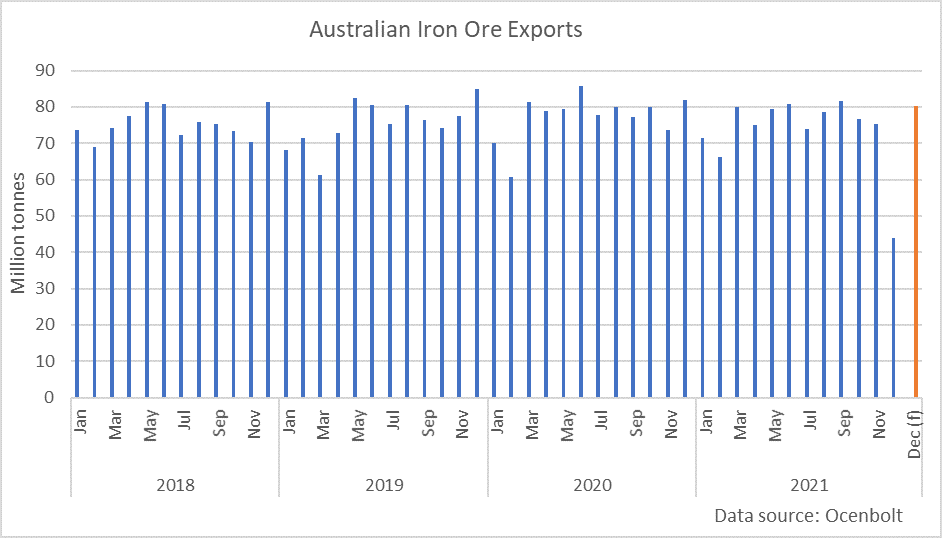

On the other hand, recent export volumes have held up better for the world’s largest iron ore exporter, Australia. The first half of the month has seen more than 40 million tonnes leaving the country’s ports, which means that it could be on track to join an exclusive group that tops 80 million tonnes. However, full-year exports are on course to fall seven million tonnes short of last year’s record 926 million tonnes.

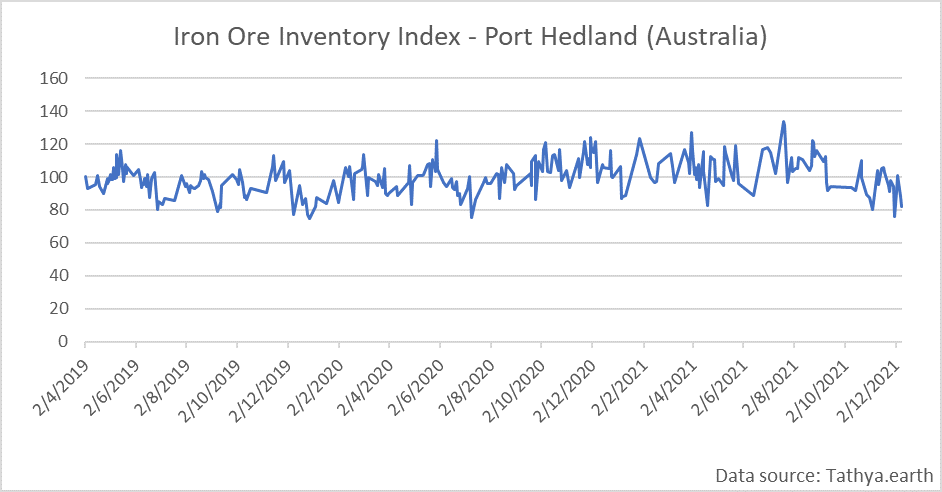

Unlike in Brazil, portside iron ore inventories in Port Hedland have been trending lower during the second half of the year. In recent weeks, the stockpiles in Australia’s largest port for iron ore shipments have shrunk to the lowest levels since July last year, suggesting that export volumes may soften in the near future.

The diverging developments for the portside iron ore inventories in the world’s two largest exporters of the commodity could see a pick up in tonne-mile demand in the Capesize segment if Chinese imports remain robust. An opportunity to source more of the steel-making ingredient from Brazilian mines, at the expense of Australia, would no doubt delight Chinese buyers in the current diplomatic climate. It would also triple the distance the shipments need to travel and tie up the vessels employed in the trade for much longer.