Drybulk freight rates have been hammered down lately. In this article we will look at the main drivers behind the drop and whether it is reasonable to expect that these effects are temporary or if we should expect them to last into next year.

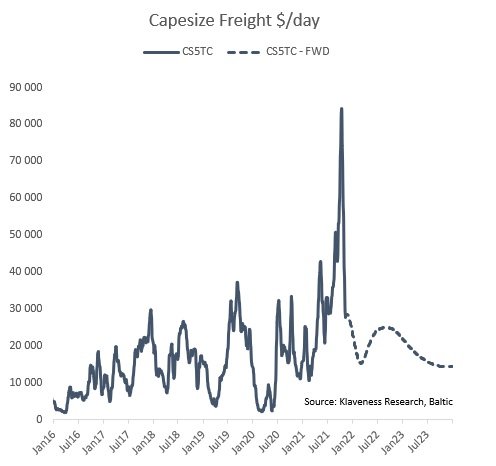

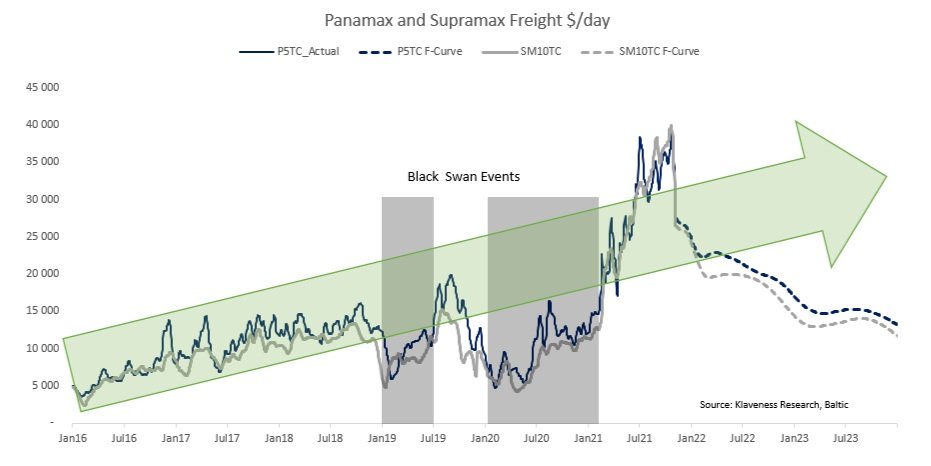

Let’s start by looking at how dry bulk freight rates have developed in the last couple of years.

Freight rates have been trending upwards since Q1 2016

Dry bulk freight rates bottomed out in Q1 2016 and have since been trending upwards. However, the underlying positive trend has been masked by two major black swan events: the Brumadinho dam disaster in 2019 and the Covid epidemic hitting the world economy in 2020 (top right graph). This year we are seeing a broad-based growth in the demand for dry bulk commodities.

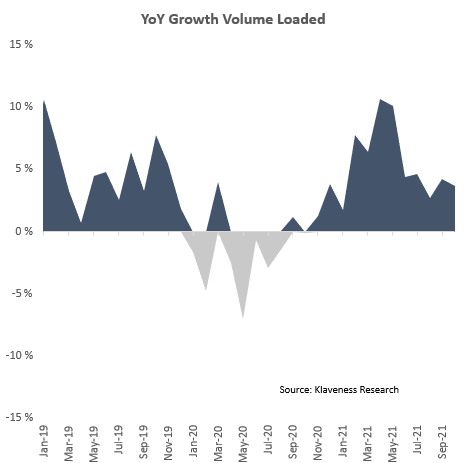

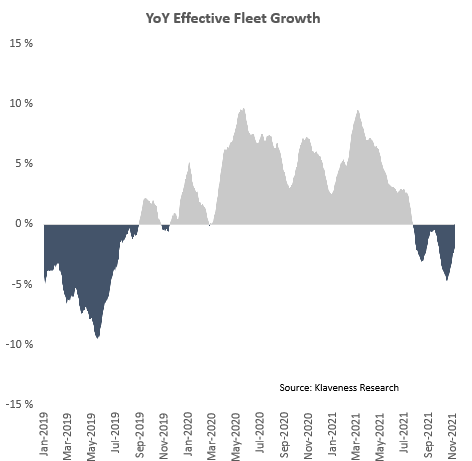

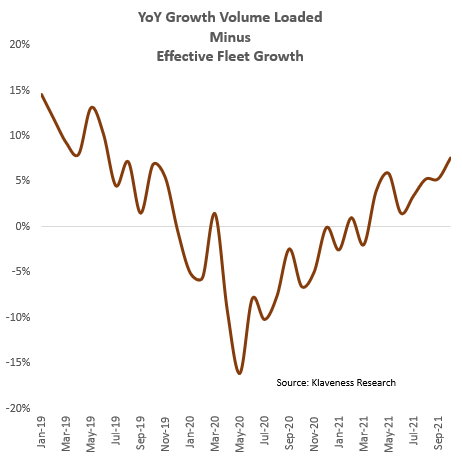

All the major commodity groups of iron ore, coal, grains, and minor bulks are recording positive growth numbers and total dry bulk volumes loaded is up 5.6% year to date (below left). Combined with low fleet growth this has led to rapidly increasing freight rates (above graphs). Although dry bulk freight rates surged in the first half of 2021, we argue that they were still within the trend starting in 2016.

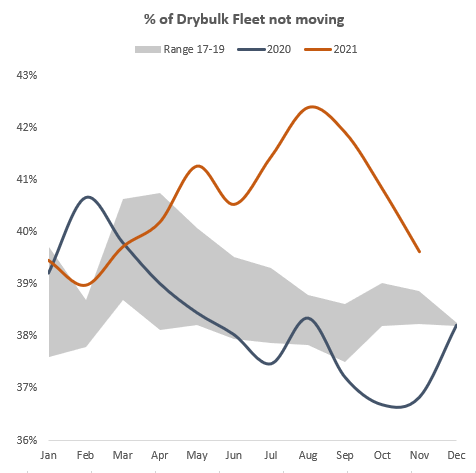

As we entered Q3, congestion started to increase quickly and meant that effective fleet growth turned negative (middle graph below). Negative effective fleet growth combined with a robust demand growth led to a very favorable market balance in Q3 and freight rates consequently rallied further before peaking in mid-October. While freight rates in the first half of the year were within trend in our view it’s not hard to argue that the freight levels in Q3 were above trend (at least not in hindsight…).

Since mid-October we have seen a steep correction in spot rates and forward values.

What are the underlying reasons for the steep correction the last 3 weeks?

We are not sitting on all the answers, but we have some hypothesis of the main reasons for the correction in freight rates seen lately.

1) A weaker sentiment linked to negative growth in Chinese Steel Production

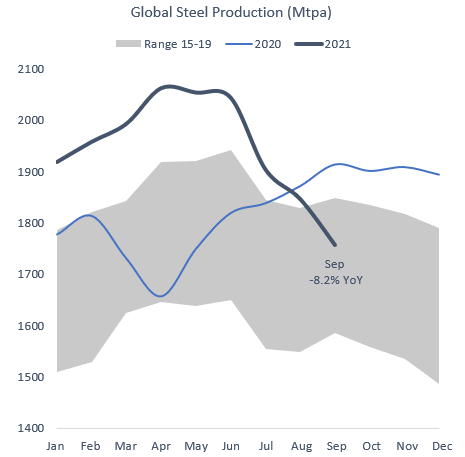

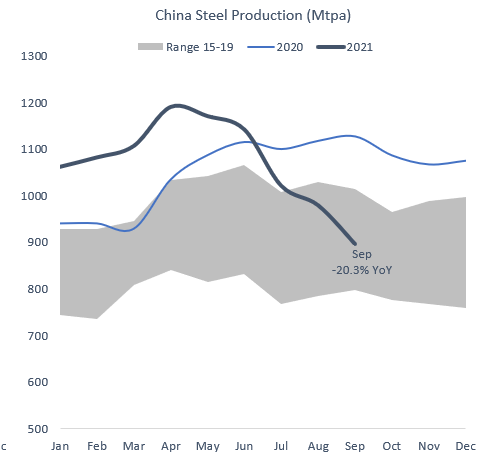

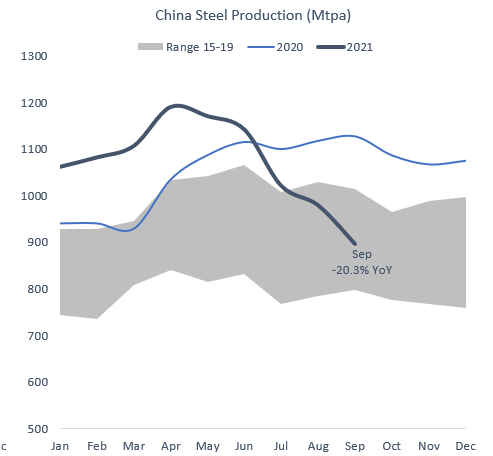

Chinese steel production recorded a stellar growth of 12% in the first half of 2021. However, since July, steel production has declined sequentially and recorded a negative year on growth of 20.3% in September (middle graph below). As China produces more than 50% of the steel in the world, this sharp change also led to global steel production correcting from a 14% growth in the first of the year to a negative year-on-year growth of 8.2% (below left graph) despite still strong growth numbers in the rest of the world (below right graph).

Why has Chinese steel production slowed down? The main culprit seems to be a softening real estate market. The Chinese real estate market is estimated to account for about 40% of Chinese steel demand, so a slowdown in this sector will have a big effect on overall steel demand in China. Another important factor is China’s goal to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy. The Chinese government has stated several times that they want zero growth in steel production this year. This seemed extremely unlikely just some months ago but now these goals are clearly within reach.

As of September, the year-to-date growth was at 2.8%. This implies that steel production in Q4 needs to be down 8.4% YoY to reach the zero-growth target for the full year. October steel production in China is still weak based on numbers coming out from the China Iron and Steel Association. Thus, the zero-growth target for steel production is not a limiting factor anymore as there is plenty of room for steel production to increase sequentially from here.

A third reason for the slowdown in Chinese steel production is the energy crisis. Steel production is energy intensive and at a time of crisis it is more important to preserve energy for private households than steel consuming companies.

A fourth reason might be the upcoming Beijing winter Olympics where the Chinese government will ensure Blue Skies. However, we don’t think this is a big driver for the cuts seen now. The reason is that these cuts will be more region specific and should not impact steel production for the country as production can ramp up in other regions, offsetting targeted cuts in steel production around Beijing.

As China accounts for about 70% of the seaborne volumes of iron ore there should be some risk priced in in terms of Chinese iron ore demand in 2022. This has clearly impacted sentiment negatively. However, we argue the restricting factor for the iron ore trade at the moment is the supply side, not the demand side. Thus, lower Chinese demand does not necessarily mean lower volumes of seaborne trade.

In the first ten months of this year, global iron ore export is up a meagre 0.7%. This has happened in a year where the spot iron ore price has averaged 167$/ton, a level where all seaborne exports of iron ore are massively profitable. This clearly shows that the limiting factor for the seaborne trade of iron ore is the supply side. The active contract for iron ore is currently trading at 93$/ton. At this price it is only high-cost Indian iron ore and some marginal Australian producers that are loss making. All other existing export capacity is in the money and so will new capacity coming from Vale and others be. Thus, we expect the seaborne trade of iron ore to remain resilient in 2022 despite potentially lower demand from China.

However, except for Vale there are not many mine expansions in the pipeline either, so we expect global volume growth in the iron ore trade to be muted. Nevertheless, the growth in the long-distance trade from Brazil to China will add a lot of ton mile and we think the iron ore derived demand growth will exceed the fleet growth.

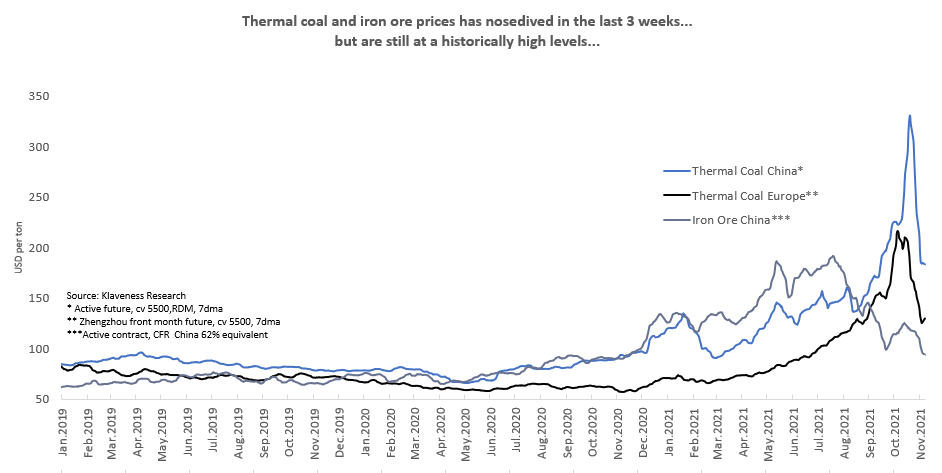

2) A sharp correction in commodity prices

The active ore contract has corrected down from a level of about $200/ton in July to 93$/ton as of today. The main reason for this has been the slowdown in Chinese steel production. Thermal coal prices have corrected sharply lower since mid-October (below left graph) when the Chinese government intervened and put a cap on coal prices while at the same time pulling all available levers to increase domestic coal production.

When commodity prices nosedive like this all traders and those end users who can afford to wait steps back and wait for the fall to run its course. Only when a bottom is perceived to be near will demand from these buyers resurface. Thus, during a price fall the actual purchases of commodities will be less than the underlying demand as those who can afford to wait, will wait.

As for now the Chinese government has succeeded in bringing the coal price down through the interventions. The latest communicated price threshold for the benchmark CV 5500 thermal coal mine mouth price is at 900 yuan per ton, which is not that far away from the front month future CFR China. This has stabilized the thermal coal prices in the last week. This alone should be enough for some end users to resurface. Once prices trend upwards then the traders and more of the end user will be out with fresh requirements in addition to pent up demand.

Is there any reason for coal prices to increase from here? We think so. While the Chinese government has succeeded in increasing domestic coal production considerably in a short period of time, this has happened in a period where demand has been (fairly) stable. Now winter is coming. Thus, we believe there still will be a deficit of coal in China and the rest of the world in the coming months and years. As with iron ore, we argue that the bottleneck for the seaborne trade of coal is supply, not demand. Thus, we expect the seaborne trade of coal to be resilient in the coming year. However, as with iron ore we do not expect a big growth in the seaborne trade either, as the number of greenfield or expansion projects are limited. Nevertheless, we expect the coal driven vessel demand to exceed the all-time low fleet growth in the coming two years.

3) A rapid decrease in congestion

The percentage of the fleet in congestion, i.e., vessels not moving at anchorages or in ports, was at very high levels in Q3, but has since been decreasing sequentially over the last three months (above right graph). The trend has been most pronounced in the Pacific where congestion is down 11% just in the last month.

When congestion decreases it releases vessels into the spot market and thus increases the effective fleet growth. The sharp decrease in congestion is clearly one of the main reasons for the weakening market since mid-October. But why has the congestion decreased? We believe the primary reason is the aforementioned sharp correction in commodity prices, which has led to less new cargoes being loaded, while discharges continued at a high level. As commodity prices show signs of stabilizing we think that congestion will bottom out and start to increase again.

4) Charterers holding back on nominating cargoes

Finally, we have the short-term effect of charterers holding back on nominating vessels. While the previous point was on new purchases of commodities not being made, this one relates to previously signed Contract of Affreightments (CoAs). A charterer who is sitting on a contractual obligation to move a commodity from A to B has a laycan window (typically 1-2 weeks) which gives them some flexibility around when the vessel needs to be nominated. When freight prices are falling the charterer is incentivized to hold back on nominating the vessels for the cargoes, if possible, as this will lower their freight cost.

Thus, actual cargoes being circulated in the market since mid-October will be lower than underlying demand for vessels. However, this can only last for so long as the charterer needs to nominate a vessel within the laycan period. This mechanism is, to a large extent, what is driving the strong tendency of mean reversion in freight rates. When spot rates bottom out, the held back nominations will resurface and rates tend to increase quite quickly again.

Summary

The rapid decrease in freight rates lately can be explained by hypotheses we’ve discussed. While risk should be priced in for Chinese iron ore demand due to point 1, we argue that the seaborne trade of iron ore is restricted by supply not demand. We see points 2, 3, and 4 as temporary effects.

Based on the above we are optimistic for freight rates in the very short term and into 2022. At the time of writing (Nov 8th, 2021) the next calendar year contracts for Capes, Panamaxes and Supras are priced at a (fairly) steep backwardation to this calendar year. All time low nominal fleet growth combined with a resilient demand outlook makes us believe that the upside risk is greater than the downside risk given the current dry bulk forward curves.