We’ve seen some lofty earnings forecasts bandied about recently for next year’s tanker market. We are bullish too, but not that bullish.

By Henry Curra

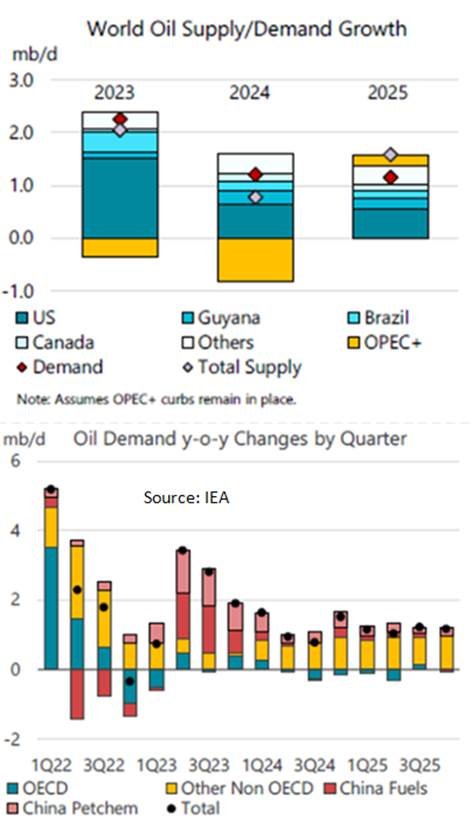

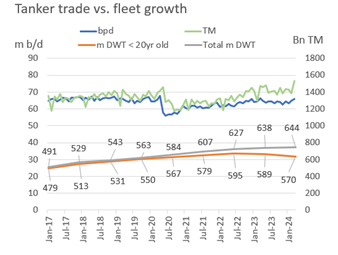

From the perspective of oil demand growth vs. tanker supply growth, we concede things look good. Taking the mid-point of the IEA’s and OPEC’s forecasts, oil demand could grow 3.25% over the next two years. Assuming a continuation of today’s chartering age restrictions, the tanker fleet would grow by just 1.8% (0.6% this year and 1.24% next year). Indeed, VLCC capacity could shrink by 0.9% with only 4 units due to deliver between now and the end of 2025.

The evolving relationship between oil production and oil demand could fuel that strength by adding to sailing distance. Oil demand is expected to grow fastest in Asia Pacific (up 4.7% over the next two years according to the IEA) whereas supply growth will be focused on far flung wells in the US, Guyana, Brazil and Canada. At some point China will need to re-build its crude oil stocks from today’s depleted levels, boosting seaborne trade. And geopolitics, that has introduced so many inefficiencies into today’s tanker trades, could get more complicated (and certainly less predictable) if Trump regains the Oval office. A return to pre-pandemic trade patterns would produce a very different set of TCE returns - notably because seaborne exports are still below their pre-pandemic levels. But this is unlikely, in our view.

To top it all, this year’s bearish themes are looking a little less bearish. The Dos Bocas refinery in Mexico and Dangote’s in Nigeria were expected to cut exports of crude oil in both regions, and imports of refined products. Instead, Dangote is now tying up VLCCs and Suezmaxes on lengthy demurrage, and Dos Bocas looks set to lengthen US supply chains when it eventually starts. Tighter sanctions on Iran’s ageing shadow fleet could open the door for Saudi Arabia to release more oil into the international spot fleet.

Enter the mega-bulls

So if markets are strong this year, the logic follows, then next year should be stronger still. $90k/day is quite possible as a spot average for VLCCs next year, say the bulls.

At today’s VLCC NB prices, the promise of anything below $55-60k for several years is unlikely to draw much investment away from the bond market. And without investment in new ships, tanker market balances should tighten beyond 2026, assuming (as we do) that tanker demand keeps growing up to and beyond 2030.

But we are talking about 2025 here. And from where we sit, tanker supply in 2025 will be sufficient to avoid sustained super-spikes, even for the under-ordered VLCCs.

Part of our argument is that, after several years of building containerships, bulkers and gas carriers, yards are pivoting back to tankers. While VLCC deliveries will be unusually light, by 2025 shipbuilders will be churning out near record numbers of smaller ships from MRs up to Suezmaxes.

As such, after several years of being king of the hill thanks to Russian exports, Suezmaxes will have to compete harder with VLCCs. This competition will intensify if the US tightens sanctions on Russia, which it should be more inclined to do post-US elections. Clean cargoes on maiden voyages of the 33 NB Suezmaxes delivering next year might delay their impact on crude tanker rates. But newbuilding Suezmaxes comfortably outnumber the 19 vessels hitting 20 years old next year. Fleet growth is assured.

Aframaxes will probably be less of a nuisance to Suezmaxes than Suezmaxes will be to VLCCs . The 52 Afra/LR2 NBs entering the fleet next year will probably match the number of ships hitting 20 years old. Demand growth for Afra/LR2s is broadly positive. LR2s are benefitting disproportionally from Red Sea diversions and new Middle Eastern refining capacity this year. But this demand boost is unlikely to repeat in 2025. Dirty-trading Aframaxes should benefit from rising TMX volumes out of Vancouver, but they could lose out to bigger ships as more crude flows long-haul between the Atlantic basin (and West coast north America) and Asia Pacific – at least until India takes over from China as the main driver of crude oil demand growth.

Take VLCCs, for example

While perhaps within the grasp of an eco–scrubber VLCC, an average TCE across all VLCCs in excess of $60k/day over 2025 would be an exceptionally strong market by historical standards. It would require most of the usual supply and demand ‘buffers’ to have been largely exhausted. We are not there yet.

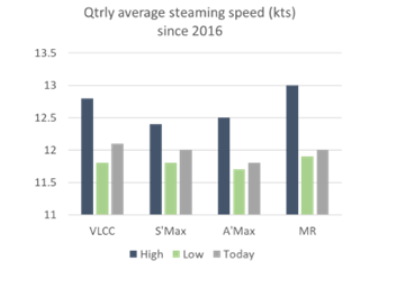

For one, average speed has room to increase. EEXI may have cut the maximum speed achievable by some (mostly older) tankers, but there remains plenty of room for manoeuvre. The VLCC fleet averaged (laden and ballast) 12.8kts during the super-spikes end 2019/early 2020. Speeds during the strong market in Q1 this year averaged 12.1kts. Tanker speeds today are just 20% off the bottom of their 2016-2024 range. Speeding up is therefore likely to keep spikes short. A longer-term acceleration to say, 12.5kts, could theoretically grow VLCC capacity by 4% - equivalent to about 35 additional vessels

When rate spikes present themselves, charterers also still have plenty of levers to pull. First, they will hide cargoes, as demonstrated once again by Chinese VLCC fixtures in the Mid East this week. Then they will delay cargoes. Then they will loosen self-imposed age-restrictions to increase the pool of acceptable ships.

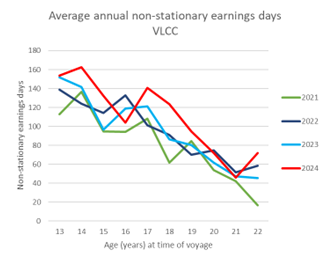

The mega-bulls would argue that charterer age-restrictions have already relaxed considerably. To a certain extent they would be right. Charterers who, a couple of years ago, might have rejected tankers over 14 years old are now regularly entertaining offers from 17 or 18 year-old ships. But utilisation of these older vessels is still well below the average for modern eco ships.

On average, non-stationary earnings days (i.e. excluding floating storage employment) for 15-19 year old VLCCs have risen by a third since 2021, from 89 days to 119 days today (derived from voyage tracking tools, which are imperfect). An under-15 year old VLCC is on track to average 159 non-stationary earnings days so far this year. Bringing the 15-20 year old fleet utilisation up to the modern average could effectively add another 36 VLCCs to the fleet.

Retirement delayed

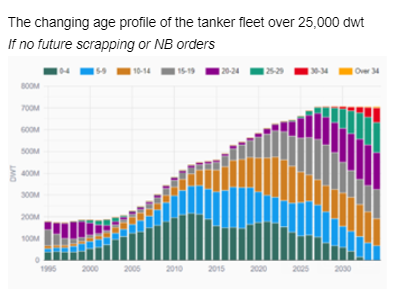

There is also the possibility that mainstream charterers could, under certain circumstances, tap into the CAP 1-rated fleet over 19 years old. There will certainly be no shortage of tonnage in this age bracket. Almost all tankers hitting 20 these days are undergoing a life-extending 4th Special Survey. Frustrated demolition brokers will complain that many tankers are doing a 5th Special Surveys at 25.

The tanker market is no stranger to fixing ships over 19 years old. In the late 1990s almost half the tanker fleet was 20 or above. The single-hull phaseout removed most of them during the 2000s and the fleet remained almost exclusively under 20 for the following two decades. When sanctioned oil exporters like Iran, Venezuela and Russia opened a range of niche ‘shadow’ trades, the over-20 fleet began to grow once again after 2020.

It is reasonable to assume that few of these older tankers will head for the beaches over the next two years. Indeed, Russia-trading tankers are finding willing non-sanctioned trading buyers on the second-hand market. As such, a full 18% of the world tanker capacity is likely to be over 19 years old in 2025.

Twenty- and twenty-one-year-old tankers currently do less than a third of the ‘cargo moving’ work of a modern tanker. They can be worked harder. Pressure from banks (trade finance) and shareholders keeps most oil majors and traders out of the market for over 19-year-old tonnage. But with so little growth expected in the capacity of modern-eco tonnage this year and next (for VLCCs especially), this ‘under 20’ rule could come with increasing exceptions. It will not be done lightly, but then nor will supporting a sector-average spot TCE return above $60k/day, in our view.

Tweaking the world’s oil trade

Finally, there is the trade itself that could shift in response to red hot freight markets.

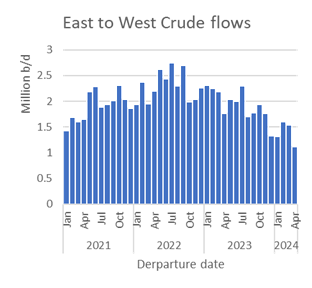

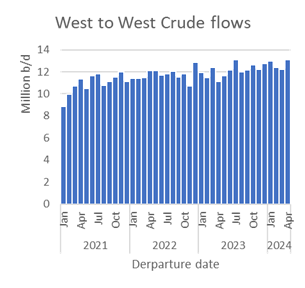

Red Sea diversions have added tonne miles, but they have also shown that, for crude oil at least, some long-haul trades simply don’t need to work. Mid East to Atlantic basin crude flows fell in line with Mid East OPEC output cuts after 2022. But the decline accelerated when Houthi rebel attacks raised the cost of Westbound shipments. Since last December westbound crude flows have fallen by a third year-on-year, from 1.76m b/d to 1.16m b/d. Flows within the Atlantic basin made up for the loss, up nearly 6% over the same period.

Buffers intact

So we suggest that the usual levers will be in place next year to quickly return lofty freight spikes to the ground. So far this year TD3c has surpassed 55k/d for just six days for a BITRA standard eco VLCC. It has found a floor at around $35k/day and averaged $43k/day. Recent spikes (post-financial crisis) above $55k/d have only ever been accompanied by heavy use of floating storage—which seems unlikely in the next two years given OPEC’s new-found discipline.

From now on the world’s refineries typically work harder, and rates should improve. Paper markets expect earnings to average $44k/d for the balance of the year, followed by $45k/day next year. The 2-year timecharter rate for the equivalent eco VLCC without a scrubber stands today at $51k/d, partly reflecting a triangulation premium that has historically stood around $6k/day over TD3c.

We expect spot TCE returns for the VLCC sector as a whole to average $54k/day this year, up from $51k/day last year. Using today’s bunker spreads, that would imply $59k/day for an eco-vessel burning HSFO (34% of today’s VLCC fleet), $54k/day for an eco VLCC without a scrubber (13% of today’s fleet), $52k/day for a non-eco VLCC burning HSFO (17% of the fleet) and $47k/day for a non-eco VLCC without a scrubber (47% of the fleet).

We expect a combination of global demand, trade efficiency and the growth of ‘useful’ tanker capacity (where charterers make better use of older ships) to weaken the sector very slightly to $53k/day next year.